Rising financial pressure on student mental health

What the future of higher education funding means for undergraduate wellbeing

The long-awaited Augar review of post-18 education funding in England has finally emerged. In less unusual times, this important announcement would have attracted a massive amount of interest. However, these are not usual times for the UK and so it has attracted less attention than one might expect. But is it actually that important after all?

Those expecting root and branch reform – such as a move to more marketization in the sector, or maybe a return to a world of low fees or low interest rates – will be sorely disappointed. Additional funding for further education and the reduction in university fees to £7,500 might initially be welcomed, but the sting in the tail is that the student loan repayment period will be extended from 30 years to 40; there is a lowering of the income threshold above which the loan must be repaid and no alteration to the punitive interest rates . One assessment shows that a graduate on an average income will actually repay around £12,000 more than under the current system. This will surely encourage wealthy parents to pay the fees up front, leaving the rest to deal with an increasingly impractical and financially unsound system. Only the poorest students are likely to benefit from the proposed grants, with the “squeezed middle” being squeezed even more.

For the universities, this also seems to be an unsatisfactory halfway house. There are vague statements that expensive courses will attract additional funding, but the level of this is yet to be defined. There also remains the risk that some universities will continue to over-recruit students to increase income while providing a worse service to them, devaluing their degrees in a competitive marketplace. We have already seen a significant number of universities scale back their capital investment plans, which in many cases will leave students living and studying in substandard facilities. Many institutions are now focusing on improving the efficiency of their existing estate and ensuring that they are delivering the best possible service for their students – no bad thing in itself, but there is a risk that even the funding for this will be insufficient and will leave legacy issues.

We have already seen a significant number of universities scale back their capital investment plans, which in many cases will leave students living and studying in substandard facilities.

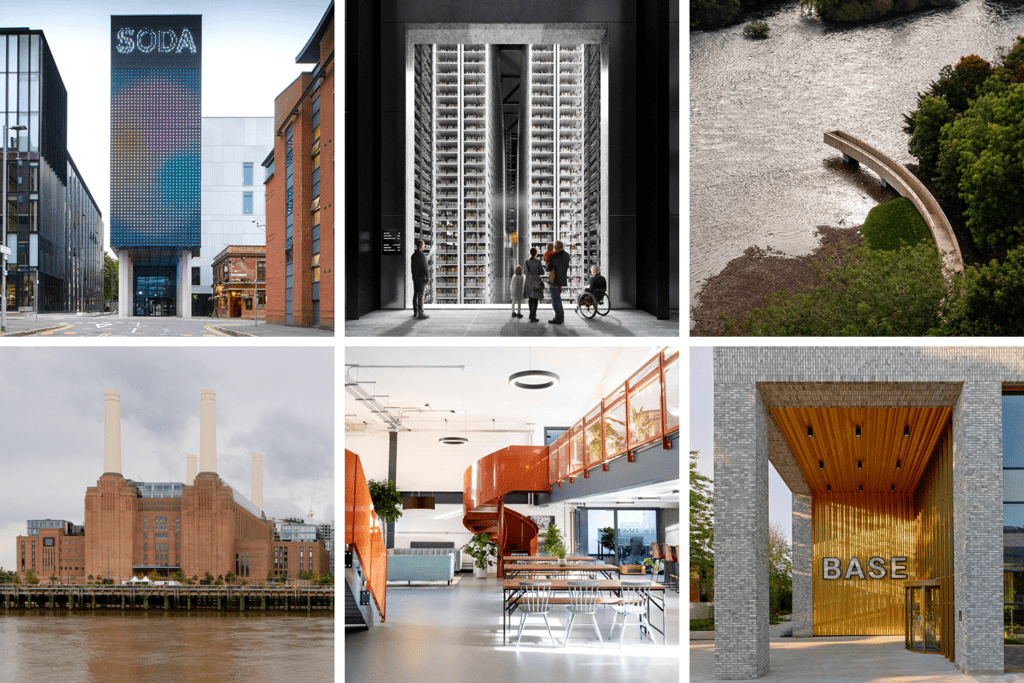

So what does this mean for the development of a university’s estate? At Buro Happold, we have undertaken a series of high-profile refurbishments over recent years, including UCL’s Institute of Education and Bartlett School of Architecture, the David Attenborough Building in Cambridge, and the soon-to-be completed Fry Building for the University of Bristol. These valuable assets all had significant environmental and functional challenges – our design skills and analytical space modelling tools are improving comfort, energy efficiency and space utilisation. The outcome is quality facilities in buildings that were often previously disliked by their occupants.

BuroHappold’s specialist energy consultants are working across a wide range of campus-scale projects to improve resilience, save energy and reduce carbon emissions. In a world where the young are highly climate-aware, this approach hits financial, environmental and ethical targets.

More than ever, universities need to take care of their students and the proposed financial model is not likely to reduce mental health issues in the sector.

More than ever, universities need to take care of their students and the proposed financial model is not likely to reduce mental health issues in the sector. In addressing this matter, it is important to appreciate that mental health is increasingly viewed in terms of a spectrum encompassing all possible conditions from flourishing to mental disorder. Most people do not remain static on this spectrum throughout their lives. Accordingly, as designers and researchers we need to adopt an inclusive “population approach” that does not focus only on those who are suffering. We must go beyond the prevention and treatment of mental ill health to target the positive end of the spectrum and avoid inadvertent stigmatisation of some students. Our unique Design for Mental Health programme has uncovered principles and issues that we are using in our designs to ensure that they promote human interaction, make it easy to get around, and provide inspirational environments. Everyone can benefit from spaces that nurture an optimal mental state.