Designing to improve student mental health

Good mental health matters. This is the message that is increasingly being heard, and listened to, by government, employers, teachers and universities. Amongst the most high profile examples relating to this issue are university students.

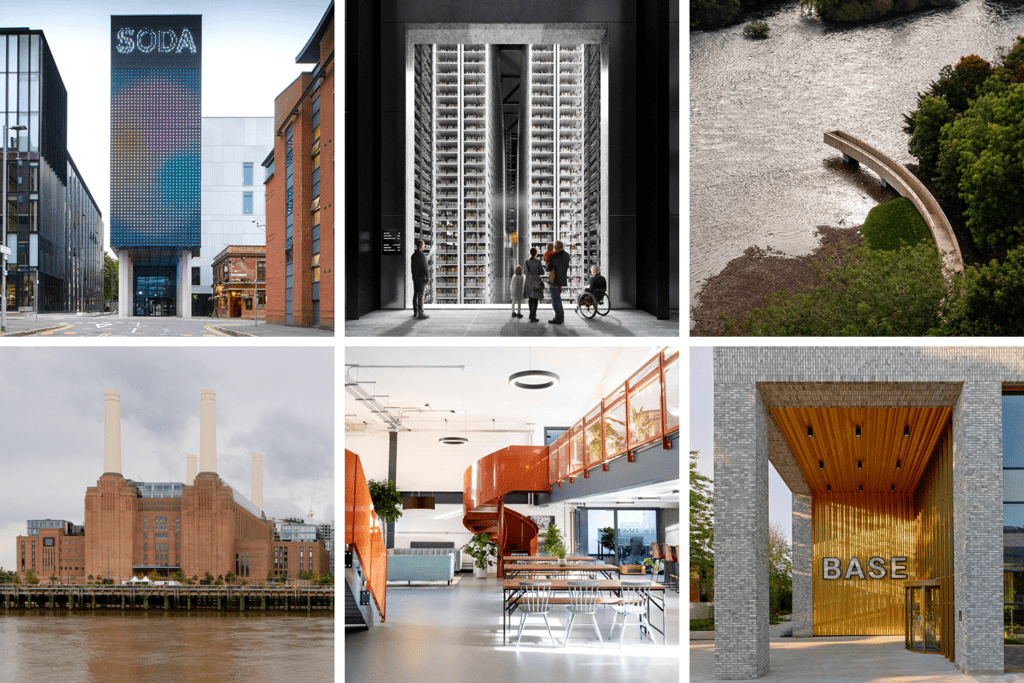

Away from the support of family and friends, the pressure of adapting to a new lifestyle, with all its academic, social, and financial pressures, is often too much to cope with. Very little research is being done to investigate how the physical environment influenced and affected the mental health of students. Bringing together multidisciplinary teams, we ran sprint events to discuss and co-create design solutions that address the critical issue of student mental health. Having kicked off the programme in the UK in late 2017 we have held three events – one each in London, Edinburgh and Manchester. In order to gain a truly global view on this, we now plan to expand our programme to ‘sprint’ in carefully chosen locations across the globe.

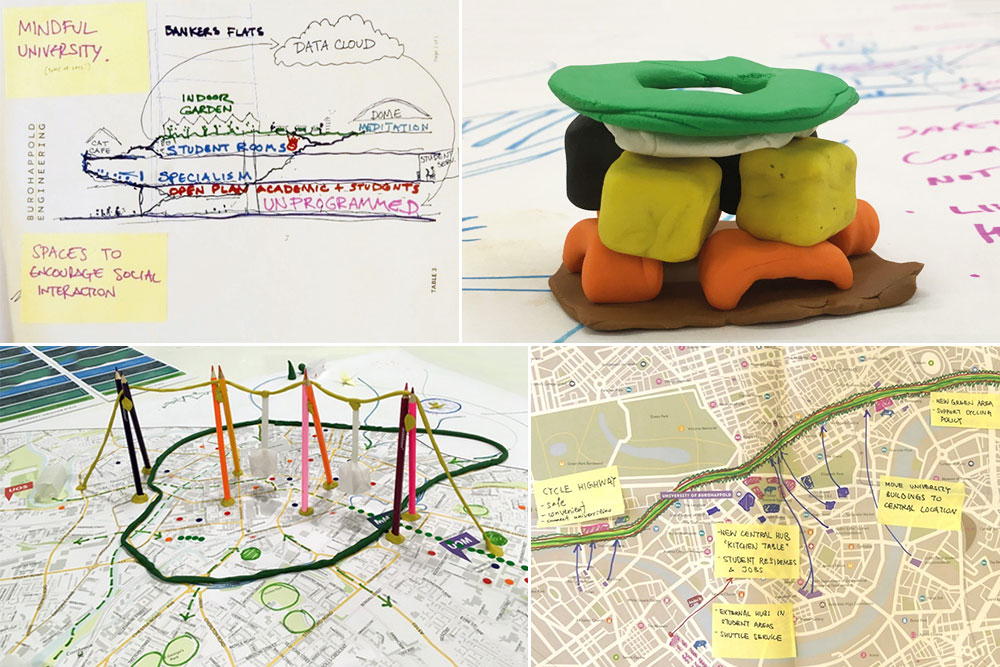

Working at a range of scales, from individual spaces up to city context, key issues highlighted include the promotion of interaction and connectivity, access to support, optimising space allocation to simplify movement, and ensuring that the quality of the environment that people move through is given as much priority as the formal learning spaces. Building on our existing international research programme within the higher education sector, it’s been fascinating to join together with collaborators, student support practitioners, and broader influencers to discuss how we can create spaces that enhance mental wellbeing for students.

What are design sprints?

Buro Happold adapted the Google Ventures (GV) process for answering critical business questions through design, prototyping, and testing ideas with customers. Usually held by Google over five days, Buro Happold condense the process into four hours. However, remaining true to the multi-disciplinary nature of sprints, we ask a broad range of disciplines to join the sprints. We also follow GVs’ lead by asking teams to address a specific challenge within a tightly defined context.

The teams generate design solutions ranging from the pragmatic to the visionary, and while many of these ideas might be considered fanciful, they highlight important issues which can be addressed in a myriad of ways to improve outcomes.

Which disciplines made up the sprint teams?

Our design sprint team participants were drawn from a wide cross-section of society to provide a mix of views and experience. The teams included: Directors of estates and facilities, Architects, Student welfare officers, Directors of property management, Student residential officers, Politicians, Psychologists, Mental health charities, Landscape architects, Students (past and present), People flow designers, Estate development managers, Design engineers, Sustainability experts, Urban designers, Heads of space planning, Inclusive design experts, Economists, Transport planners, Academics.

Ongoing education sector international research programme key outcomes

In 2015, Buro Happold began researching the role university estates play in the business of higher education and the academic experience. The ongoing study gathers together the views of vice chancellors and estate professionals from 20 interviews and survey data from just over 1300 UK and 3000 US students, to identify and address key topics.

Through our US and UK student surveys, we know that students have a strong preference for well-connected spaces within buildings, in between buildings and at a campus/city scale. We also know that students prefer green, landscaped campuses and buildings that provide ample daylight along with reduced noise and thermal comfort control.

We know that the built environment is not the only factor contributing to good or poor mental health, and we do not pretend to have answers to this complex issue. We do however have a responsibility to design spaces in and around universities that provide the best possible opportunity for students to be physically and mentally healthy, happy and productive.

The changing nature of higher education and its environments

In May 2018, Buro Happold hosted a one-day higher education planning sprint with executive directors, vice-presidents, and campus planners of higher education institutions in the USA to discuss the challenges universities face in relation to their physical space.

The aim of the event was to discuss that despite the rise in virtual learning everywhere, physical campuses still matter. Technology and lifestyle changes have, however, fundamentally changed the types of space being designed, the way students move between places of learning and the desirability of being in campus style universities, as opposed to those set in a city context.

Session 1: Technology and space needs: The way campus spaces are being used is changing dramatically. Large classrooms are, in many places, being abandoned in favour of remote learning or smaller interactive spaces. These spaces range from libraries to informal open spaces where people can be “alone in public.” Transforming existing spaces is not easy to do, and funding constraints exist everywhere. Sharing labs and co-locating other university spaces with third parties or other universities needs to be further explored.

Session 2: Connectivity and mobility: Geographic contexts vary widely across American universities, and hence mobility and connectivity needs vary as well. Traditional mobility planning has focused on more sustainable forms of transportation – buses, bikes and walking. Some universities are, however, questioning the need for movement between distant parts of campuses and are exploring techniques to minimise it, including synchronous learning – where one teacher simultaneously teaches two classes.

Session 3: Urban regeneration: Increasingly, American universities are being seen as regenerative forces in their communities. Historically, these universities have not capitalized on mixed-use opportunities to increase utilisation of their downtown spaces. Today, a number of universities located in suburbs or exurbs of towns are moving downtown – some adaptively reusing historic structures and using placemaking to attract and recruit new students.

Further work is being undertaken to address the areas of interest of our participants and broader issues affecting the sector in the US, including the nature of car utilisation, autonomous vehicles and parking, the future of libraries on campus, student mental health, and the operation of public-private development relationships in areas that go beyond their traditional territory of student accommodation. With a wealth of information from our range of outreach and consultative programmes, we are focused in our support for universities as they seek to attract and serve students and researchers in a competitive world. A short paper addressing key areas is likely to be developed as part of the upcoming SCUP (Society for College and University Planning) conferences.