What impact does the climate crisis have on water resources?

Faced with a climate crisis, effective management of water has never been more important. In the latest of our specialist consultant Q&As, we spoke with our water experts to discuss the impact the climate emergency has on our relationship with water.

Water is at the heart of discussions of sustainability and the climate crisis. At Cop27, water was the focus of a dedicated thematic day. To learn more, David Palmer and Paul Brenton spoke to us about the water related problems the world faces because of the climate crisis, and the engineering choices we can make to reduce flood risk and manage water effectively and efficiently.

What are the challenges we are facing because of the climate crisis?

David Palmer: We’re facing huge increases in population growth, combined with changes to our rainfall patterns. Rainfall patterns are changing and are less predictable than they were previously. Storms are frequently more intense and have a shorter duration, resulting in more runoff, less infiltration to the ground and increased flood risk, with less groundwater recharging our aquifers.

Paul Brenton: Living near the sea has always been somewhat hazardous due to the risk of flooding and erosion from storms. This is certainly true of the UK, but internationally there are even greater hazards if you live in the path of tropical cyclones (typhoons and hurricanes). We know about the human cost of such events. The sea is such a powerful, dynamic force. With climate change, those risks will significantly increase.

Combined with the ongoing migration of people toward the coastline, this means the increased hazard applies to more people and more property. The chief concern is rising sea levels. Apart from the obvious risk, this will also mean larger more powerful waves at the shoreline. Warmer seas will mean that storms will become more intense, as we’ve seen over the last decade with some of the most destructive tropical cyclones in history.

David: With changing weather patterns, occurrences of serious flooding are increasing. The recent floods affecting large parts of Europe resulted in 243 deaths and more than €10bn of building damage. The floods in Pakistan this year followed an extended period of heatwave. The results were horrific, with 1,700 deaths, including 639 children.

In all, floods since June 2022 have affected 33 million people in Pakistan and rebuild costs are estimated to be equivalent to 10% of the country’s GDP. Since the shattering flood in Pakistan, there have been floods resulting in loss of life the world over; Spain, the US, Australia, Chad. The list goes on.

What impact can our work have in areas of the world that require sustainable water management?

David: Water resource management is the process of minimising demands and finding the most sustainable sources of water to match those demand points. Making water go further, more efficiently is the best way of making things equitable; true equity starts to spread through the management of water.

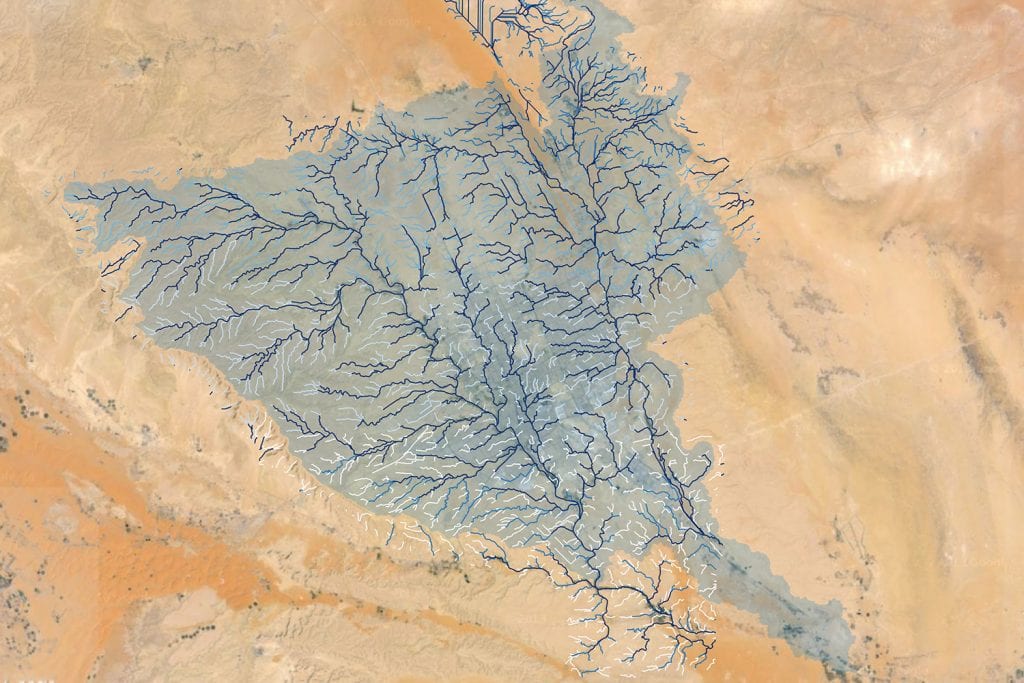

When it comes to our work in the Middle East and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, one of the good things is that, as engineers, we are able to work on a much broader scale, well beyond the footprint of an individual building, and almost regional scale.

Making water go further, more efficiently is the best way of making things equitable; true equity starts to spread through the management of water.

David Palmer

Being able to work beyond the building footprint means that we are able to influence a far greater portion of the water cycle. Our ability to reduce flood risk through upland catchment management increases, we can increase rates of infiltration to the ground, we look at ways to increase the recharge of our aquifers. Similarly, as we work on a broader scale, we are able to make use of the wider options that are available in terms of water resource management.

What else can Buro Happold do to mitigate flood risks?

Paul: Redevelopments of historic harbours are interesting cases. The repurposing of old harbours has been an ongoing process for many projects across the UK. We have led on many around the UK, in Plymouth, Cornwall, Folkestone and most recently on the Mersey for Everton FC’s new stadium.

These are stranded assets right at the heart of communities, waterfront sites that can become catalysts for wider regeneration. The challenge with that is that harbours are built quite low for functional reasons and pre what we now know about sea level rise; if you want to build there, they’ll be vulnerable to sea level rise sooner.

Folkestone Harbour is an ongoing project for us spanning 10 years; there’s a development of about 1,000 new homes on redundant harbour land in a deprived neighbourhood behind the beach, so obviously vulnerable, but our work has helped make it safe for at least the next 100 years. We have done this using a very natural solution; shingle beaches protect many areas on the south coast of England and are extremely efficient at absorbing wave energy and naturally adapting to changes in sea level.

The critical thing is to have the shingle in the right place for when the next storm comes. We have worked with the client to develop a continuous beach maintenance strategy funded by the development itself – and the best thing is there is no ugly seawall to block views and people having fun.

David: We have been involved in very altruistic, hugely interesting and rewarding projects under the Buro Happold ‘Share Our Skills’ initiative. Our young engineers make use of their growing expertise and their time, for example in Kibera, which is a slum district in Nairobi, Kenya.

We’ve been going to Kibera for a few years with Share Our Skills, with members of the water team and infrastructure team volunteering on local projects that help reduce flooding (because that is essential for the communities in Kibera), capturing rainwater for reuse and improving water quality. This is really important work; I increasingly think the world is going to be changed less by my generation and more by the younger engineers who are currently honing their expertise.

How do we work with our clients to face the challenges caused by climate change?

Paul: The frightening aspect about sea level rise is that much of it is already baked in no matter what we now do about carbon emissions. The only uncertainty is the speed it will happen and what the maximum level will be. What seems certain is that in a few centuries time sea levels will be several metres higher than now, regardless of future emissions. The challenge for our clients is how to plan, protect, and adapt to how fast it occurs. On the speed, the projections vary wildly, which makes the planning part very tricky and makes the adapt part essential.

So one of the issues at the moment is trying to navigate our way through the myriad of projections, to enable clients to make informed choices about what needs to happen and when, and how they adapt. There are a lot of variables that make it hard for clients. Part of our job is to help clients plan for different scenarios to give them a roadmap that they can adapt to the inevitable changes that will occur.

David: We can look to reduce demands, not just within buildings, but within landscape programmes and agricultural processes. We can make precious potable water go further, by maximising efficient use of non-potable sources, such as treated sewage effluent, greywater and harvested water. We can even make use of groundwater, provided that we abstract it at a lesser rate than we are recharging the precious underground supplies.

Other things that we can do are less about direct engineering and more about design guidance and influencing governance.

About Paul and David

Paul Brenton leads Buro Happold’s expertise in coastal and maritime engineering. His work focuses on the unlocking of coastal sites through the application of a targeted suite of multidisciplinary engineering, planning and environmental services to realise client and architectural aspirations.

David Palmer is the discipline director for Buro Happold’s UK water team and global technical lead. He joined in 2006 and is a Fellow of the Institution of Civil Engineers. As well as working on some of the UK’s largest water projects, he has extensive experience working in the Middle East. During his time at Buro Happold, he has played a major role in leading our water resource management and flood risk management services.