As part of our latest series of interviews for The Edit Magazine, we hear from a number of our specialist consultants from across the practice.

Here we speak to Technical Director Paul Brenton, who is part of our Water Group, about what inspired him to become a coastal and maritime engineer and some of the high profile projects he has been involved in. Paul also touches on the importance of working closely with other specialists on the city system.

Sea engineering must be a very exciting environment to work in?

It is, and it’s also hugely challenging. We’ve all experienced how the sea can be calm and idyllic one moment, then turn into a seething threat to life and property the next. And it’s not just the sea, but the shoreline and beaches that can also change on every tide – even to the point of an entire building or road being lost in a storm. The coast is the most dynamic environment that humans live and play in, and that’s why it pulls us in and fascinates us.

Is that what drew you to become a maritime and coastal engineer?

I think I was always destined to be an engineer. I’m from a naval family and I grew up by the sea, spending my childhood on beaches in the southwest of England. That certainly brings home both how dangerous the sea can be and the beauty of the ever-changing natural environment. At school, my favourite subjects were maths and geography, and I love problem-solving — all of which I now encapsulate in my technical work.

How do you balance defence from the sea with the celebration of it?

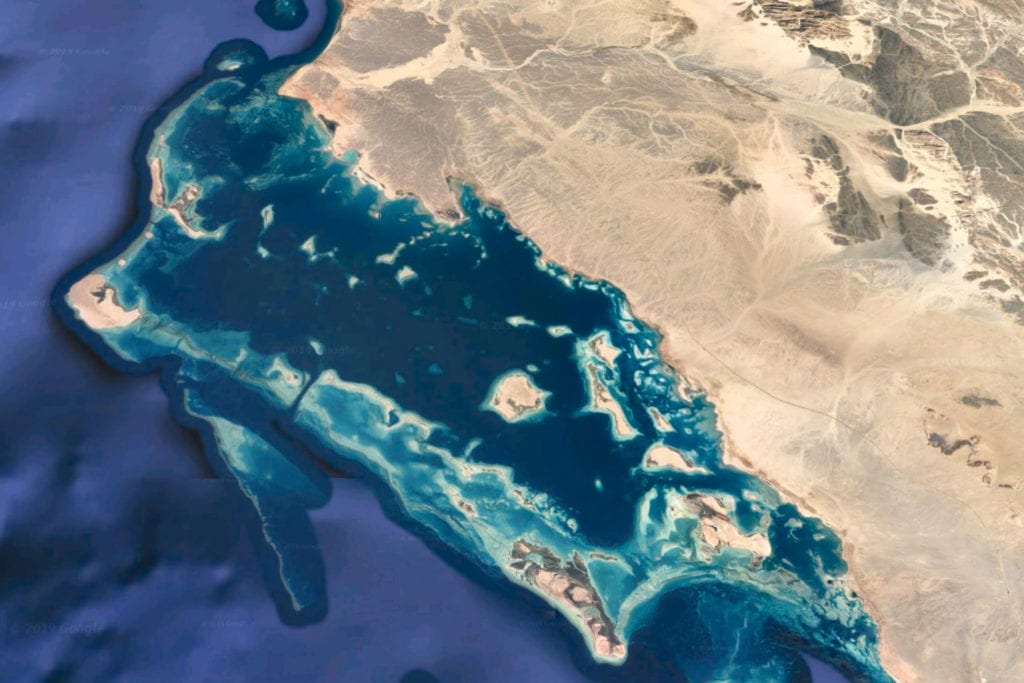

That’s a major challenge. People want to live near the sea, but in doing so we’re putting pressure on that environment and, essentially, damaging it. Because we value it so highly, we also want to protect it, and that creates real conflict. This tension is only going to intensify as more and more people migrate towards the sea and the coastline comes under increasing pressure, particularly from sea level rise. We’re seeing this on some of our Red Sea projects at the moment. Working with our environmental consultancy team, we’re obtaining data early on that helps us shape and direct development to the most appropriate places, and lessen its impact as far as possible.

Which projects are you currently involved with on the Red Sea?

The main one is AMAALA, a tourist-level led development around natural coastal bays and islands. These are incredibly sensitive environments, home to extremely rare turtles and dugongs, as well as nesting migratory birds. Our client wants to develop the area to attract people from around the world, but to balance that against the impact on what’s currently a pristine marine environment. In many ways, it’s a project that talks directly to the core issues of development at the shoreline.

How do you gather data?

In terms of the Red Sea, we’ve worked on a lot of projects up and down that shoreline so have a cumulative knowledge base that we can deploy. We also use remote sensing such as satellite derived bathymetry, which uses satellite imagery to work out the depth of the seabed. We’ve used it on all of the Red Sea projects, and it enables us to work out where the most sensitive areas are likely to be so we know where best to concentrate development, and equally, where it’s best avoided.

It seems you have to balance multiple different interests on these projects…

Yes, and that’s always complicated. By developing at the shoreline, clients aspire to realise the ‘Instagrammable’ image of the seaside on a peaceful, sunny day. As engineers, we need to also think about the typhoon that’s coming next year, or the looming threat of sea level rise. We work closely with the environment, transport and energy teams here at Buro Happold to get a full understanding of the risks involved on each project, so that we can inform our clients about them early on. This enables us to reach decisions together that maintain the vision while remaining grounded in reality.

Tensions between development and conservation are going to increase as the coastline comes under more pressure.

What’s the most complex project you’ve worked on to date?

In terms of technical challenge, it has to be Louvre, Abu Dhabi. Delivering a reinforced concrete building — reinforced concrete and salt water don’t like each other very much — that is built many metres below sea level, exposed to waves and housing priceless artwork. That was an incredibly difficult project, but ultimately very rewarding.

And the most inspiring?

That would be the regeneration of Hayle and Folkstone Harbours, which are two of the largest UK projects that we’ve done. Each project presented us with numerous challenges in terms of flood risk, contaminated ground, heritage considerations and environmental issues, but beyond that both proved to be game-changers in terms of catalysing regeneration. That’s what has been so inspiring – seeing the benefits brought to the wider community in two towns that have been through pretty tough times.

They sound like big projects…

Folkestone, in particular, is a complete cradle-to-grave project for us. We’ve been involved for over a decade, working across two masterplans and providing everything from environmental impact assessments to the supervising of construction contracts. It’s drawn on specialisms from across our Cities and Buildings Groups — including water, environment, structures, ground engineering, energy and transport. When we completed both the enabling works to protect the site from flooding, and the restoration of the historic railway core, our Cities Group handed over to our Buildings Group, who are leading the next stages. Phase one is currently being built and will create 50 seafront properties.

The coast is the most dynamic environment that humans live and play in.

Buro Happold’s structure, where energy, transportation, bridges, environment and water disciplines are grouped, allows specialisms to work together?

Yes, and the client in Folkestone really appreciated the way that enabled us to mobilise and provide a rapid response to changing situations. Our teams are very close-knit, and that means we’re able to keep on top of things and work together to help our clients make the right decisions. I think it’s this agility and responsiveness, and what that means for client care, which sets us apart.

What’s next for the Water Group at Buro Happold?

I think we’re in a strong position to meet the challenges facing us, which are only going to get bigger with population growth, increasing migration to the coastline, and the desire to create new places for people to live and holiday in. We’ve got an amazing portfolio of projects behind us, and a great team that we’re looking to expand, so I’m really excited for the future.

Our teams are close-knit, and it’s this agility and responsiveness that sets us apart.