The way we move around our cities is changing rapidly. But the way we design our streets has not changed at the same pace.

The rise of micromobility as a global trend has been somewhat unexpected and, even if tackled from a legislative and regulatory perspective, the street requirements for these modes are still not fully developed or addressed.

Cities across the world are working towards more sustainable and equitable transportation networks. However, our cities are still largely designed for cars and existing guidelines for urban planners are centred on bikes and bike lanes but fail to incorporate a wider range of transport modes.

With two thirds of the population predicted to be living in our cities by 2050, methods of transportation in urban spaces need to be reconsidered if low carbon emission goals are to be reached. Public transport can move huge numbers of people every day, but it is not always accessible. Where there is a lack of alternatives, citizens turn to private cars, contributing to pollution, traffic congestion and parking issues.

Below we set out a 10-point vision that promotes the modal shift from motorised to non-motorised vehicles. Highlighting the micro-mode’s convenience and flexibility, and pushing towards a micromobility-based urban environment.

1. Make big data on micromobility open source for both users and city planners

This will allow city planners to use heat maps to understand where improvements can be made, as well as allowing users to choose their travel route based on real time information about the current condition of streets.

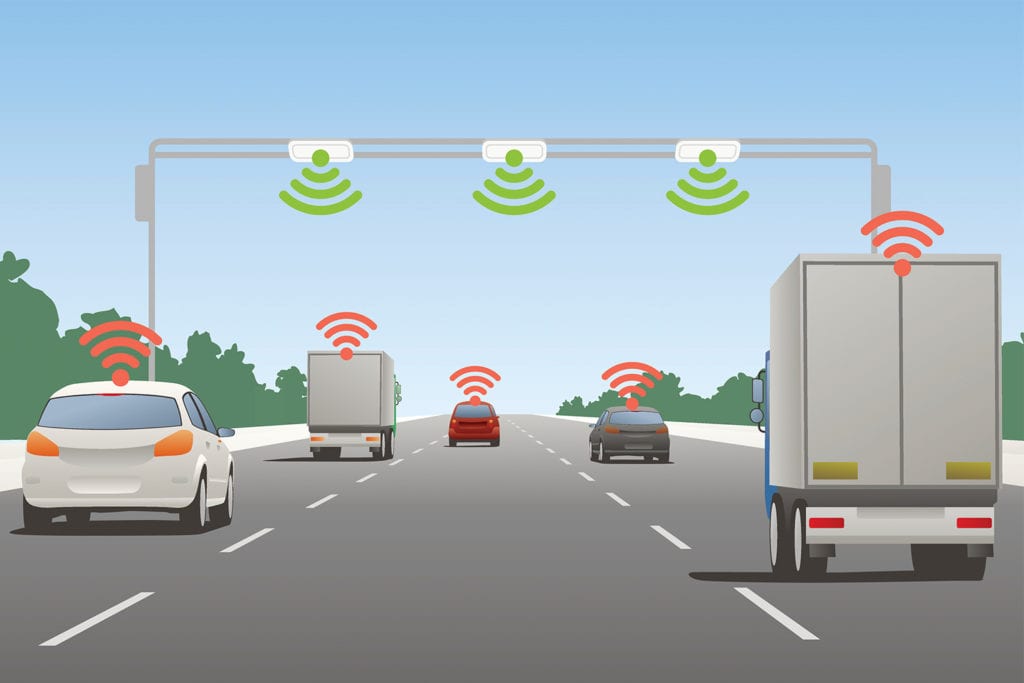

2. Integrate autonomous technology within micromobility

This would help to reduce congestion and encourage people to share car journeys. There is potential for people to use their smartphones to hire driverless vehicles to reach their destination.

3. Create a city-wide GPS system to allow for a “green wave” traffic signal

The system would recognise approaching micromobility vehicles and inform a signalised junction to switch to green, allowing micro-modes to proceed instead of cars.

4. Create micro-priority junctions

This would ensure micromobility vehicles are the main stakeholder approaching a junction. The CYCLOPS junction in Manchester is an example of this.

5. Develop a clean cycle map

This map would include colour-coded lines and hierarchies, indicate interchanges and display main movement directions.

6. Adapt public transport for micromobility users

Seating areas on public transport could be revised to accommodate bikes at low peak periods. This would allow for all micromobility to travel seamlessly between different networks and extend travel distances.

7. Establish consolidation centres for deliveries

City centres are congested due to the next-day delivery model. Consolidation centres could be built on the perimeter of city centres with micromobility vehicles used to make the last mile delivery.

8. Create an inclusive system

A Mobility-On-Demand (MOD) system that uses Ubers and taxis for short-term journeys would create an accessible option for those who normally would not cycle and could allow for access to certain places that are not permitted for cars and public transport.

9. Allow for additional modules

Attachments could be made for different micromobility vehicles such as trolleys for groceries, tandem modules for couples and covers for different weather conditions. Helping to ensure this form of travel is always a viable option and accessible to all.

10. Adapt essential spaces

Retail ground floors have been re-organised to allow for social distancing which has allowed space for the carriage of smaller personal micromobility modes and could be maintained in the future.