Climate change mitigation: tackling the rising temperature of our cities

In the second of two features focusing on thermal impact in urban environments, Buro Happold Associate Director and Building Physicist Daniel Knott addresses the danger of rising temperatures in our cities.

The heat is on for our cities. Over 55% of the world’s population now live in urban locations, and with this figure set to soar to 68% by 2050, life’s only going to get hotter.

Emerging from this picture is the increasing phenomenon of urban heat islands (UHIs). These pockets of thermal congestion are a direct result of the accumulation of bodies, buildings and vehicles. Add to this solar gain and the steadily rising temperature of our planet due to global warming, and the result is an unwanted, sometimes dangerous build-up of heat in urban areas.

A deep dive into Abu Dhabi

Buro Happold’s sustainability and physics team has been undertaking in-depth analysis of microclimates around the world to understand the impact of UHIs. Building on our expertise in low energy design and occupant comfort, we have developed measures that mitigate the negative effects of heat gain in urban areas, and by doing so established a new capability for our clients.

With each project, our knowledge and capability in this emerging subject has increased significantly. In a recent project in Abu Dhabi, one of the most challenging urban locations on earth, the ambition is to tackle everything from mobility and inequality to innovation and economics, with the aim of creating a city that works for the future. One of the key objectives is to make life easier and more enjoyable for all residents and, with thermal comfort a top priority, this is where our building physics team comes in.

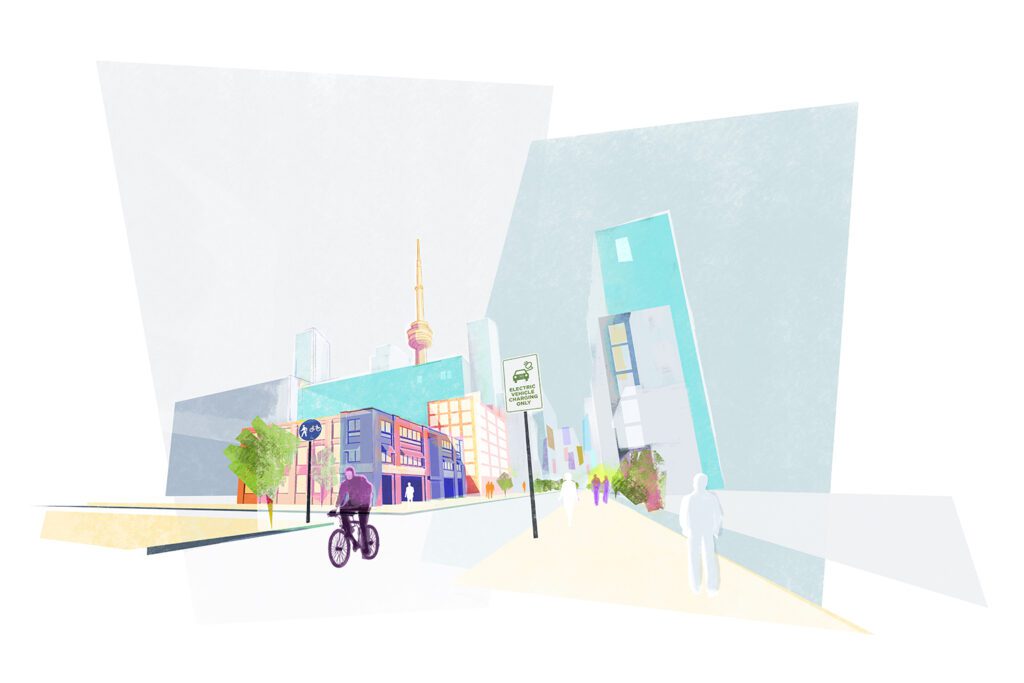

Our client wanted us to analyse various spaces across the city to create more comfortable microclimates and, in turn, mitigate the effect of UHIs. In place of hot spots, we aimed to establish areas that were significantly cooler than their surroundings, inviting people outside to enjoy life in the city. From transitional areas like sidewalks and passageways to destinations such as plazas and parks, we looked to reduce temperatures and promote walkability and liveability within Abu Dhabi.

From urban heat island to oasis in the desert

Following a twofold approach, the Buro Happold team drew from a combination of experience, computational analysis, academic studies and local weather data to develop initial design concepts. We then conducted site visits to record elements such as air temperature, radiant temperature, solar glare, humidity and wind speed, inputting this additional data into our models to further test and refine our solutions.

As so much heat discomfort in Abu Dhabi comes directly from the sun, shading was one of the first mitigation measures we looked to implement. But, as shading comes in numerous forms, it wasn’t as simple as popping up a parasol in the park.

Initially, we looked to introduce planting. Walking through urban spaces usually involves seeing lots of manmade materials that absorb the heat and reflect it back, magnifying the effects and creating an oppressive environment.

Incorporating shrubs and trees not only provides shade, but also lowers the surface temperature of areas, and regular watering further minimises the effects of heat via evapotranspiration. Because it can take 10 years for newly planted trees to establish and provide adequate levels of shade, we adopted a hybrid approach in some areas, introducing man-made shading systems that could be rolled back at night to allow heat to dissipate.

The build-up of heat from thermal mass was also an important factor to consider in Abu Dhabi. Everything from concrete buildings to tarmac sidewalks was absorbing the sun’s rays during the day and holding on to the heat overnight, resulting in a stifling, cumulative UHI effect.

Compounding the problem, our studies suggested that the urban population increased through the afternoon and peaked in the evening, meaning it was an issue that affected the greatest number of people. To combat this, we changed materials where we could – replacing tarmac with lightweight wooden lattice flooring or gravel and applying reflective paint to surfaces to reduce heat absorption.

We also considered elements such as air movement and building orientation. The former can be beneficial in some locations, creating a welcome breeze that enhances cooling and comfort. But equally, the wind can transport an unwanted thermal situation from one area to another. The benefit of shading on a sidewalk, for example, can be eclipsed if the wind transfers all the heat from a busy road back onto the pavement.

We took into account the orientation of adjacent buildings to understand the changing movement of sun and air throughout the day and adapt our designs accordingly for the various sites across the city.

Benefits and deliverables

We targeted a 3– 5°C improvement across all the sites in Abu Dhabi, providing a baseline that we aim to exceed by 5–10°C in less built-up areas. As well as the clear environmental benefits of reduced heat build-up, increased vegetation and decreased car use, our work will also bring social benefits that will change the lives of many of Abu Dhabi’s poorer residents.

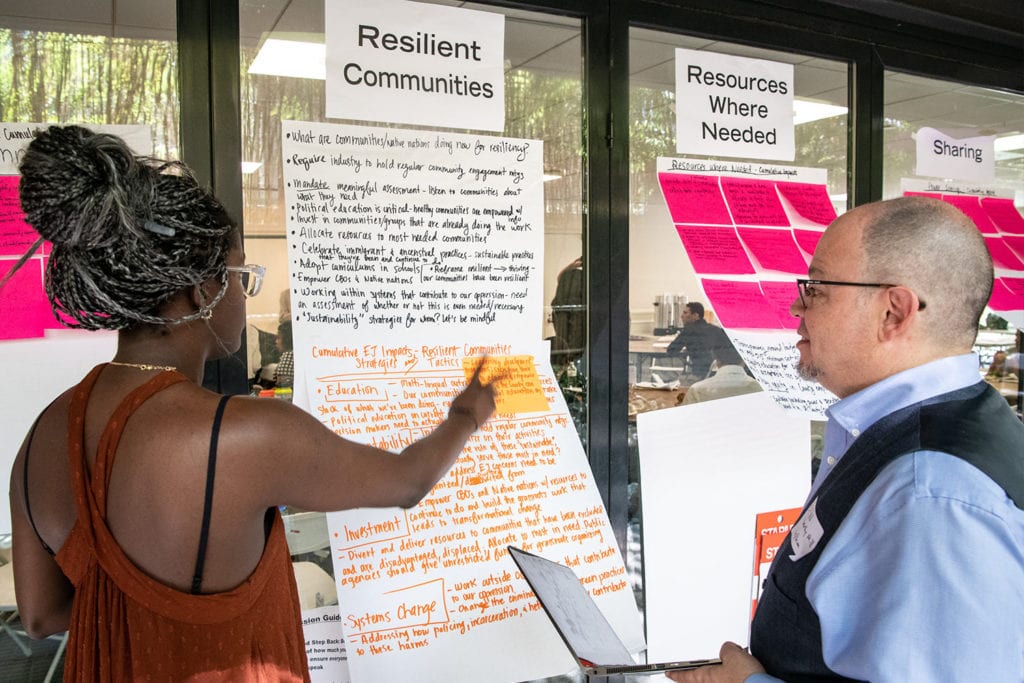

In a city designed for cars, the simple commitment to improving comfort along sidewalks and pedestrian routes will have a huge impact, providing relief from the oppressive sun and more accessible ways to cross the city. Similarly, combating the build-up of thermal mass in high density areas, where poorer people are crowded together to live and work, will improve health and wellbeing. Because of this, the very people who have been exposed to the worst situations will benefit most from these interventions.

With construction now underway on several of our heat mitigation initiatives across the city, we will begin to see the results of our solutions within the next two years.

If our predictions hold true, positive outcomes will be felt immediately and increase over time as occupants learn positive behaviours, and physical elements such as trees and shrubs grow to provide increased heat mitigation. This, in turn, will prove our analysis and pave the way for our designs to be replicated in other cities around the world, improving life in urban areas for generations to come.