Can London Bridge be the capital city’s next park?

London Bridge, which connects the City and Southwark over the River Thames, was constructed over 50 years ago. Since then, vehicular traffic using the bridge has reduced, and the generous 30-metre-wide crossing could certainly be utilised more effectively.

To combat climate change and improve the city for locals and visitors alike, London has a policy framework to increase the area of green infrastructure and urban greening. Moreover, the Covid-19 lockdowns and restrictions have shown how much we all value our parks and green spaces.

Not only do green bridges absorb and store carbon, but they also provide more notable benefits, like managing local stormwater, reducing the urban heat island (UHI) effect, improving air quality, and creating social value.

In light of the above, it is the time to transform London Bridge into a city park, giving it the attention it deserves and the urban greening London needs.

Why?

We are amidst a climate and biodiversity crisis. We need to take serious action now to combat the effects of climate change. We must reconsider building new infrastructure and find new uses for our existing bridges and structures. We must find ways to reduce our carbon footprint, absorb atmospheric carbon dioxide and improve the biodiversity in our environment.

London has a policy framework to promote green infrastructure in the city, called the “All London Green Grid“. Part of this framework is to increase the amount of urban greening around the city. The Mayor of London’s goal is to have over half of the city green by 2050. To meet this challenge, we will need to be creative, ambitious and reconsider ideas that have been dismissed as non-starters.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, we became aware of how much green spaces are valued by society.1 They became a refuge from the restrictions and being confined to just the four walls of our flats and houses. Furthermore, surveys show that there is an increased demand from renters2 and workers3 to have access to green spaces where they live and work.

For example, Elephant Park became the first new park in the centre of London in 70 years, showing that whilst the demand for parks and green spaces is definitely there, the supply is short in a city with an ever increasing population. To help combat this, there is campaign by the charity CPRE London to create 10 major new parks for London4.

As previously discussed in this series of articles, London Bridge is under utilised given its size. London Bridge is 32-metres-wide, and despite having four lanes of carriageway, the number of vehicles using the bridge per day has halved over the last two decades. The bridge and its surrounding area has some of the lowest natural capital in London5, i.e., the world’s natural assets, such as air, water, soil, geology and living organisms.

London Bridge no longer needs to carry a dual carriageway over the River Thames. It is primed to be turned into an urban green space.

How would this be achieved?

There are several ways we could increase the natural capital of London Bridge and quite literally, turn it green.

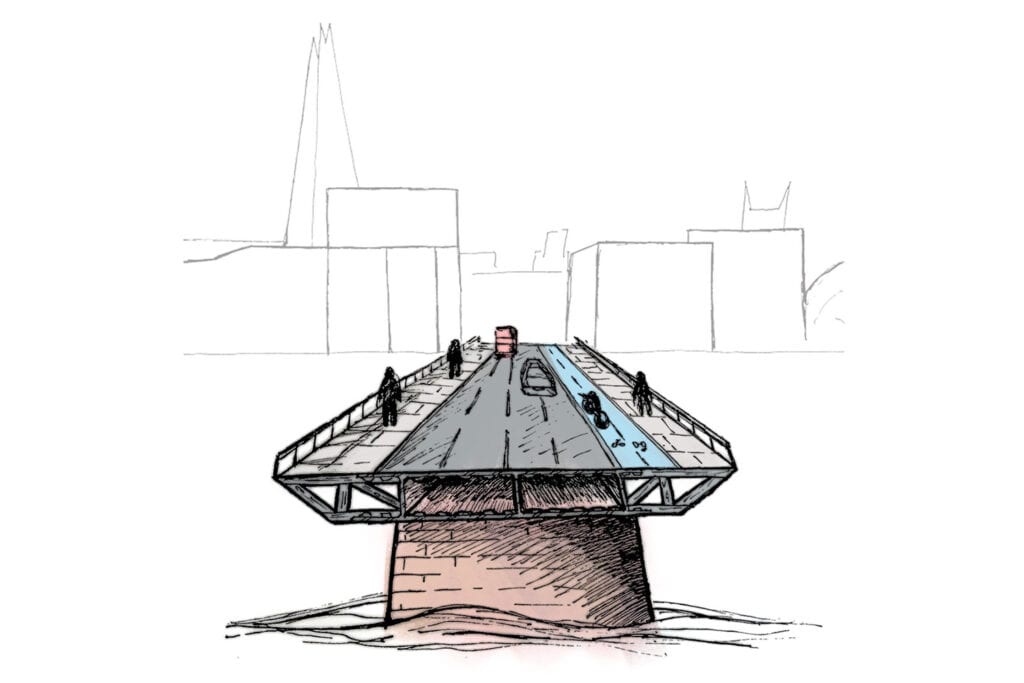

Removing two of the four carriageway lanes and one of the two footways would free up around 16 metres of the bridge’s width and make room for a park across the River Thames. London Bridge is approximately 280-metres-long, so just over an acre of space would be available to turn into green space.

There are several different ways to make London Bridge a “green bridge”. For precedents, we can look to the following best practice examples:

- The UK has several green bridges, providing a continuation of the countryside severed by busy roads. Most of these bridges are in rural areas, such as the green bridge spanning the A21 at Scotney Castle in Kent

- The City of Hamburg in Germany is planning to create a green network by joining together new and existing green spaces together that will cover 40% of the city’s area6

- The Green Bridge in London’s Mile End spans over the A11 and allows Mile End Park to extend over the A-road instead of being two halves linked via a narrow bridge

- The High Line in New York was a disused elevated railway line that has been transformed into a public park. There is also a similar elevated walkway in Paris, called the Promenade Plantée.

We are constrained, to a degree, by the form of London Bridge and it would have to be assessed structurally for whatever changes are proposed. However, as the above examples show there is a lot of potential for plants to take root and flower on London Bridge.

What are the benefits of increasing our natural capital in London?

This article series started looking at whether it was possible to have a net carbon zero London Bridge. The urban greening of London Bridge could contribute to making this happen.

However, planting trees across a 16-metre-wide bridge would only absorb about 2.2 tonnes of CO2 per year,7 and 25 centimetres of deep soil could store about 8 tonnes of carbon for each 1% of organic matter in the soil8. This is not very significant when our own personal annual carbon footprint is 4 to 5 tonnes of CO2, and the construction of London Bridge has produced thousands of tonnes of CO2.

Setting aside absorbing and storing carbon, there are several significant benefits to increased urban greening.

Shading and cooling effect

Trees, shrubs and plants cool the air by reflecting solar radiation, providing shading and through evapotranspiration of their leaves. Trees and vegetation reduce the mean average UHI effect around buildings by up to 1.9˚C, and surface temperature within green spaces can be up to 20˚C lower than the surrounding area9. A green London Bridge would be cooler in the summer, making it more accessible to those who are aggravated by the heat.

Improving air quality

Vegetation reduces air pollutants by breaking down gases, such as nitrogen dioxide (NO2), in an area of London which has particularly poor air quality. Studies have shown that vegetation can reduce the concentration of NO2 by 40% and particulates by 60% in urban canyons.10 NO2 and particulates can lead to a range of health effects from coughing, wheezing, asthma, heart attacks and strokes.

Sound barrier

Soil is particularly good at absorbing noise, due to the moisture in the soil. Introducing plants and soil beds will absorb the noise from nearby vehicles, making crossing the bridge a more pleasant experience for pedestrians.

Surface water management

Heavy rain can be a serious issue for surface water flooding, which is made worse by the large covering of impermeable surfaces in our urban areas. Green areas are an ideal way to absorb and slow down the flow of rainwater. For substrates that are 100mm deep or greater, 66% or more of rainfall can be retained.11 This significantly reduces and delays peak discharge.

Biodiversity

Adding vegetation would introduce wildlife, such as bees, beetles and birds, to London Bridge. This could be used as a stepping stone to other green spaces in London.

Aside from the environmental benefits to urban greening, there are also social and economic benefits. London’s public green spaces have a value of £91B to the city,12 and every £1 spent on them provides £27 to the public. They also benefit our mental and physical wellbeing and help us make healthier lifestyle decisions13.

What next?

We will explore the topic of improving London Bridge for people and nature alike in future articles. We should all consider how we can maximise our existing infrastructure and adapt it to our current and future needs. Adding trees, plants and shrubs is a great way to do that.

In the meantime, why not read the first and second articles in our bridges series:

- Could the next London Bridge can be carbon zero?

- How can we maximise the social value of the next London Bridge?

How would you like to see London Bridge transformed? Contact us via our bridge engineering and civil structures specialism page.

Sources:

- Katharina Winbeck, Kate Hand, Ruth Knight, Andrew Jones, Peter Massini and Ben Connor. London Green Spaces Commission Report. August 2020.

- ‘Parking and green space most sought after property features for London renters’. Property Reporter. 17 July 2020.

- Steven Lang, Simon Preece and Rob Pearson. ‘Spotlight: The Rise in Demand for Green Space’. Savills UK. 21 November 2019.

- Alice Roberts. ‘Let’s create ten major new parks for London, now!’ CPRE London. 20 November 2021.

- Map of London’s Natural Capital. GLA Maps.

- Kaid Benfield. ‘Hamburg’s Ambitious Green Network Addresses Nature, Climate Resilience, Sustainable Transportation’. Smart Cities Dive.

- ‘Greenhouse Gases’. Trees In Trust.

- Bobby Whitescarver. ‘Five Dollars a Ton for Carbon’. Whitescarver. 25 June 2019.

- Doick et al. ‘Keeping London a Cool Place to Be: The Role of Greenspace’. Papers and presentations from the 2014 Trees, People and the Build Environment II conference. 2 April 2014.

- ‘Green plants reduce pollution on city streets up to eight times more than previously believed‘. ACS. 29 August 2012.

- Erica Oberndorfer, Jeremy Lundholm, Brad Bass, Reid R. Coffman, Hitesh Doshi, Nigel Dunnett, Stuart Gaffin, Manfred Köhler, Karen K. Y. Liu and Bradley Rowe. ‘Green Roofs as Urban Ecosystems: Ecological Structures, Functions, and Services’. BioScience. November 2007.

- ‘New figures reveal £91billion value of London’s parks and green spaces’. Heritage Fund. 23 November 2017.

- ‘Urban Green Space Interventions and Health – A review of impacts and effectiveness’. World Health Organisation. 2017.