It is no accident that communities of color are often clustered in areas with the greatest exposure to air pollution, the least access to economic opportunity and the poorest health outcomes.

These inequities are the direct result of discriminatory housing and land use policies that intentionally segregated communities throughout the twentieth century. If we do not take active measures to right these wrongs, this form of white supremacy will become the legacy of the twenty-first century as well.

In the United States — not unlike many other countries across the globe — there is a sordid history of redlining. During the Great Depression, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) was established to stabilize the housing market. The HOLC programme relied upon lenders to determine where to approve home loans. Those lenders rated neighborhoods based on their ‘desirability’, a thinly veiled code word for racial discrimination.

People of Color (POC) were excluded from purchasing homes in predominantly white areas and faced barriers to securing home loans, buying property and accumulating wealth that could be passed on to the next generation. This was exacerbated by other discriminatory practices such as racially restrictive covenants, which prohibited homeowners in white communities from selling or renting property to people of certain races, ethnic origins and/or religions.

Unable to buy property in ‘desirable’ neighborhoods, many People of Color (POC) moved to areas that had less access to jobs, high quality schools, health care, nutritious food, parks, recreation and other factors which increased the intergenerational wealth gap. On average, white families have nearly eight times of their black counterparts today.

Though banned in 1968, the practice of redlining entrenched inequality and public disinvestment in ethnic minority communities. As a result, many of these communities still face higher levels of environmental pollution that impact their economic, physical, and mental health.

For example, it is the formerly redlined neighborhoods that experience the greatest urban heat island effect today, driven by sparse tree canopy and an abundance of heat trapping surfaces, in addition to being targeted by planners for highway construction and industrial land uses1. Koreatown in Los Angeles — the redlined neighborhood where my own family immigrated in the 1970s — is one of the most population dense and park poor areas in the United States.

Redlined neighbourhoods also face increased exposure to criteria air pollutants that affect residents’ respiratory systems. This has had a devastating impact on health outcomes, including those related to the Covid-19 pandemic.

The pandemic has been shown to be more severe in communities with long-term air pollution exposure, a finding consistent with previous links to air pollution and infectious disease outbreak severity.2 While Covid-19 has decreased US life expectancy for white men by eight-tenths of a year in the first half of 2020, this figure was three years for black men.3

Sadly, environmental racism and housing discrimination are far from extinct. Land use decision-making processes are political in nature and often bend towards the interests of homeowners with time, money and political influence – all of which are much easier to wield with intergenerational wealth.

Power plants, waste transfer stations and transitional housing are amongst the infrastructure that continue to face opposition from white neighborhoods, despite being critical to societal function. There are also overt instances of People of Color (POC) being shown fewer homes by real estate agents, or receiving much lower home appraisals in comparison to when they ask their white friends to pose as the homeowner.

Perhaps most famously, the predatory lending practices represented by subprime mortgages not only contributed to a global economic downturn, but imposed economic stress on many of the same neighborhoods which have been unfairly targeted.

What Buro Happold is doing

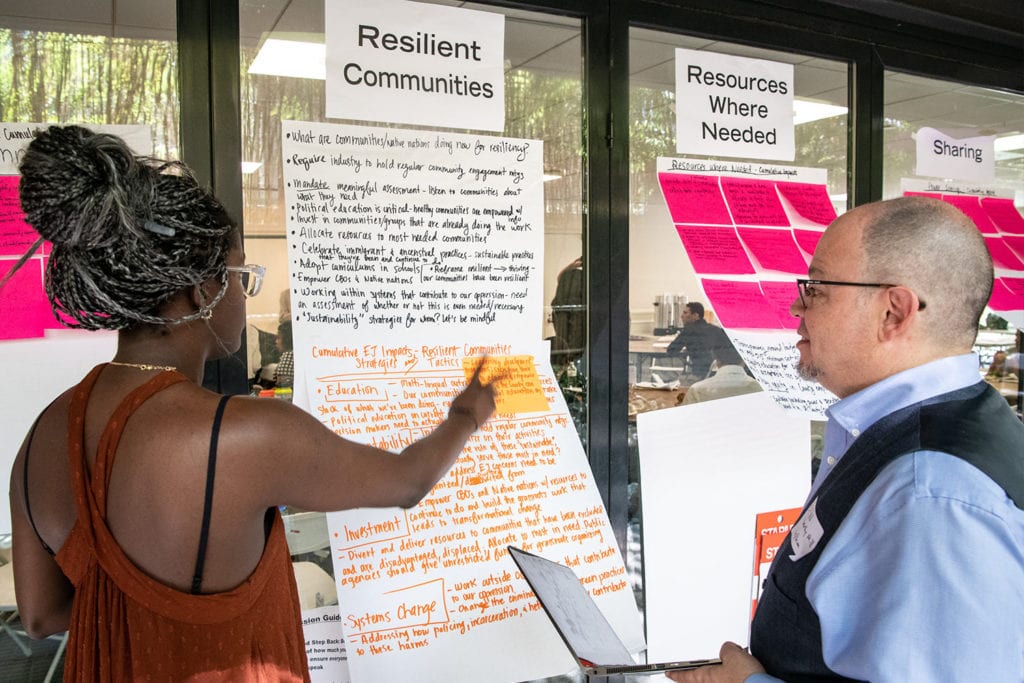

Placing equity at the centre of urban planning discussions is essential to ensure just outcomes for our communities. We must provide access to equal opportunity and achieve positive health and wellbeing outcomes for all residents – regardless of race, class, religion, gender, age, disability, sexual orientation or residency status.

While various definitions of equity have been used by public agencies and non-governmental organizations, most are organized around a set of lenses that guide the development of public policy to address the needs of the most disadvantaged communities and individuals.

In the North American Cities practice, we generally refer to the Urban Sustainability Directors Network (USDN) Equity Scan Steering Committee definition as presented below. Equity in sustainability incorporates the procedures, distribution of benefits and burdens, structural accountability and generational impact. This includes:

- Procedural Equity – inclusive, accessible, authentic engagement and representation in processes to develop or implement sustainability programs and policies.

- Distributional Equity – sustainability programs and policies result in fair distribution of benefits and burdens across all segments of a community, prioritizing those with highest need.

- Structural Equity – sustainability decision-makers institutionalize accountability. Decisions are made with a recognition of the historical, cultural and institutional dynamics and structures that have routinely advantaged privileged groups in society and resulted in chronic, cumulative disadvantage for subordinated groups.

- Transgenerational Equity – sustainability decisions consider generational impacts and do not result in unfair burdens on future generations.

In addition, we refer to the racial equity as a key lens, focusing on an end state in which race can no longer be used to predict life outcomes. This ensure outcomes for all groups are improved.

Confronting the impacts of redlining and other forms of systemic racism must continue to be a major aspect of our work at Buro Happold. We must bring environmental justice to the forefront to ensure a sustainable and equitable future.

Sources: