Climate resilience and the intersection with urban equity

The climate crisis has necessitated work on climate resilience and adaptation. Here, we consider the intersection of urban equity with climate resilience – and the role played by the built environment.

The climate crisis

The climate crisis continues to shock, impact and change all our lives. It has environmental, economic and social implications. Environmentally, we can consider rising temperatures, extreme weather events, and food and water insecurity. We already see the impacts upon global supply chains, urban infrastructures, water supplies and energy systems. Health outcomes, livelihood insecurity and climate migration are social impacts.

A highly visible example is the is wildfires in Canada in June 2023 that severely affected the mid-west and east coast of the US, with extremely poor air quality and visibility in cities like New York, Chicago, Washington DC and Boston. These cities are home to many millions of people, who at the height of the fires were advised to wear N95 masks to protect themselves. Residents in Quebec had to be evacuated away from the fires.

The built environment plays a critical role in helping to curb and prepare for supporting global approaches to climate change. A key area is the sheer impact of the built environment on the climate; work to decarbonise buildings and associated ecosystems continues apace. Another area of focus, which does not always receive the attention it should, is how work within our industry can build and support climate resilience.

What does climate resilience mean for the built environment?

Climate resilience and climate adaptation are different but connected concepts. Adaptation refers to the change required within processes, systems and infrastructure to live with the climate crisis. Resilience involves the capacity to anticipate, withstand and cope with the shocks and impacts caused by the climate crisis to our social and economic systems. There is naturally a degree of crossover between the two.

Within the built environment, we have a sphere of influence that includes climate resilient urban infrastructure and development. At Buro Happold, specialist services include climate hazard assessments, and climate adaptation and resilience strategic planning.

While mitigation efforts and decarbonisation work must also happen to slow down and reduce frequency of higher temperatures and more extreme weather events, climate resilience work looks more closely at the impacts and how the world must adapt.

Sabrina Bornstein, principal and regional discipline leader, Buro Happold

Sabrina Bornstein is a principal in our Los Angeles office and Buro Happold’s regional discipline leader for cities. She is greatly experienced in the area of climate resilience and represented Los Angeles in the 100 Resilient Cities Network and the C40 Cool Cities Network. Since joining Buro Happold in 2019, her work has involved vulnerability assessments, resilience strategy and climate policy. She was climate adaptation lead for West Hollywood’s Climate Action and Adaptation Plan and led the Los Angeles County Climate Vulnerability Assessment as well as support services for Silicon Valley Clean Energy’s Community Energy Resilience program.

Sabrina said, “The 100 Resilient Cities Network considers climate resilience as the ability to survive, adapt and thrive in the face of chronic stresses and acute shocks.

“While mitigation efforts and decarbonisation work must also happen to slow down and reduce frequency of higher temperatures and more extreme weather events, climate resilience work looks more closely at the impacts and how the world must adapt.”

Inequitable impacts

Climate justice and equity are core to our climate resilience work. Not everyone experiences the impact of climate change in the same way. We are not all effected equally. Those with less resources to cope with impacts of the climate emergency can experience disproportionate negative effects or take longer to recover.

Vulnerabilities include historically low levels of investment, age, health conditions, income, housing situation and employment status.

Sabrina Bornstein said, “In terms of equity, we are not all going to be affected by the climate crisis in the same way. There is a disproportionate effect on individuals at the heart of the climate crisis. Age, pre-existing health conditions, access to thermal comfort or adaptations like air conditioning and social vulnerability are all differing factors.

“When acknowledging this disproportionate affect, we have to ask: how do we prioritise and deliver built environment interventions? How do we consider climate action from a place of public health?“

The word ‘urban’ in discussions of urban equity is key: one differentiator that is critical to how communities experience the climate crisis is their location. Urban environments are very different from other parts of the world and offer their own unique challenges. How climate resilience and urban equity intersects is of vast importance.

Urban equity intersection with climate resilience

Why must we dedicate consideration into how the climate crisis uniquely affects cities and urban environments? Because the impact on urban spaces requires a distinct approach; the structures, systems and infrastructure in a city is totally different to, for example, somewhere rural.

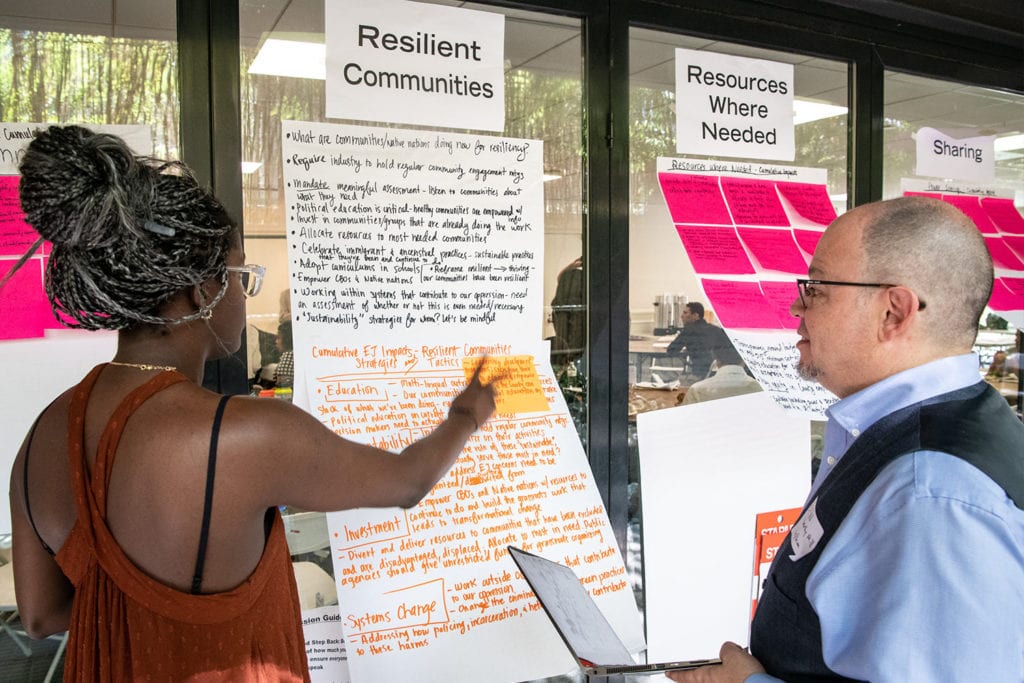

The intersection of urban equity with climate resilience is one that deserves attention; the lack of equity within urban environments in resilience efforts requires a light to be shone to highlight the different realities, needs and requirements of communities in cities.

Sabrina Bornstein considers the idea of equity and where resources should be placed. She said, “For example, I’m based in LA. Over in one community, it’s hot – but it is a community that is wealthier and more likely to have air conditioning and newer homes.

“So, is it equitable for us to put money into climate adaptation strategies there versus focusing on community where it might not be as hot but there’s a higher population of unhoused people who don’t have shelter or protection, and there is older housing stock with more people renting. Equity needs to take into account places that historically have had less investment and populations that are more vulnerable.”

Resilience shouldn’t just be considered as the after effects of something or as part of a recovery period; it is a longer-term consideration

Sabrina Bornstein, principal and regional discipline leader, Buro Happold

For example, the devastation caused by Hurricane Katrina in 2005 on New Orleans (primarily the flooding that overcome the city’s flood defence system, which destroyed homes, buildings, infrastructure, transport and communication facilities) was wrought on a city that was already affected by poverty and by unequal access to areas like education or employment opportunities.

Damage was especially severe in African-American majority neighbourhoods. Recovery from Katrina has been far slower and more challenging for the Black population of the city.

Sabrina added, “There are a lot of urban communities that have already been impacted by extreme weather events, such as New York and Hurricane Sandy, New Orleans and Hurricane Katrina. When it comes to rebuilding after events like that, it is about embedding resilience within those plans and trying to plan ahead. Resilience shouldn’t just be considered as the aftereffects of something or as part of a recovery period; it is a longer-term consideration.”

Where should the resources go?

There are also many practical considerations to why urban areas are affected differently by climate change. Sabrina said, “I work a lot on extreme heat. Within those discussions, it is incredibly important to look at cities because of urban heat islands, where the development patterns in urban areas exacerbates and amplifies heat. The same applies to floods in urban areas; many surfaces in cities are impervious which makes flooding more intense.”

Heatwaves across Asia disproportionately affect low-income populations in cities, who do not have the cooling facilities or infrastructure to keep them safe or comfortable that their more well-off counterparts may have. Indeed, those who are the most vulnerable are nearly always those who are subject to external forces such as policies and historical unequal distribution of resources. These external forces contribute to susceptibility to climate risks and ability in protecting themselves from the impact of the climate emergency. The marginalisation of some groups of people – especially visible in cities – sees them suffer the most.

Equity needs to take into account places that historically have had less investment and populations that are more vulnerable

Sabrina Bornstein, principal and regional discipline leader, Buro Happold

Climate migration – who has the means?

The idea of climate migration is increasingly becoming an area of focus. Some places on Earth will be increasingly inhospitable and are likely to see movement of people away from them. Inherent within this idea is that not everyone will have the means or ability to move: how is this equitable?

Sabrina Bornstein said, “There are certain areas and communities that will change; if you look at Hurricane Katrina, after that a lot of people left New Orleans and didn’t go back. But that is caught up with the idea of equity; who is it that has the means and money to leave and go somewhere else?

“This issues of climate migration and equity are going to be increasingly relevant in terms of how we plan to provide space for people who need to migrate due to climate change and in ensuring it isn’t just extremely wealthy people who can afford it.”

Conversely, there will be some enforced movement of people who simply have no choice; they will be displaced and become climate refugees because of climate impacts. The most vulnerable and poorest communities – who have contributed the least to climate change – are the most affected and hardest hit. This is not simply an issue of extreme weather but impacts on land use and livelihoods.

Will the landscape improve?

The disproportionate effects of the climate crisis on a wide variety of communities and the inherent equity issues are a subject that deserves more attention. However, within our own sphere of influence – through climate resilience strategies for cities and organisations, infrastructure planning and community engagement – we must do all we can.

Sabrina Bornstein said, “Ultimately for me, climate work really is about the human side. We can talk about greenhouse gas emissions, we can talk about building technologies, but at the end of the day this work (and why it’s tied to equity) has a very real human impact. We can support the reduction of that, and the disproportionate impact at the heart of it.”

Learn more about the climate change adaptation and resilience services Buro Happold offer here.