Urban resilience: planning for the worst

On 4 August 2020, a 2,750-tonne cache of ammonium nitrate stored at the Port of Beirut in the Lebanese capital exploded, causing 218 deaths, injuring 7,000 people, and exacting US$15bn in property damage. It left an estimated 300,000 people homeless.

Five years earlier, the Municipal Council of Beirut, in collaboration with the World Bank, had launched the City Resilience project to develop a Comprehensive Urban Resilience Masterplan. Recognising the city’s importance to the country and wider region, Buro Happold reviewed the key hazards facing the city, identified gaps in response and recovery planning and went on to formulate an integrated, multi-sector strategic plan to address both asset-based and community risks.

But the 2020 explosion was a reminder that the biggest threats to urban resilience come from so-called Black Swans – unpredictable catastrophic events. It is not generally imagined that Black Swan events will come along together. We tend to make the mistake of thinking of them as once-in-a-century risks that we can deal with in isolation. But a catastrophic fertiliser explosion striking in the middle of a global pandemic was a sobering reminder that it’s not necessarily how it works.

For Beirut, it was one more disaster after half a century of instability. But threats of this magnitude, whether from disease or terrorism, accident or natural disaster, are not just an existential threat for less stable nations. Post-pandemic and with climate change challenges increasingly at the top of municipalities’ agendas, cities across the world are waking up to the reality that strategic planning around multiple scenarios can be critical in ensuring a swift response and recovery when the worst happens.

As a UK government consultation, led by the Cabinet Office, was drawing up a new “National Resilience Strategy” this autumn, Labour peer Lord Harris of Haringey, told The Telegraph (September 25, 2021) that Black Swans are not Whitehall’s only concern. “There are Black Jellyfish with multiple tentacles which go on longer than you expect and have a nasty sting in the tail. Plus Black Elephants, the thing nobody wants to talk about’,” he quipped.

He also pointed out that there are 38 risks in the latest National Risk Register, but they are all in siloes. What isn’t recognised is that one could trigger another in a cascading effect – for example, a loss of power leading to petrol pumps not working. But at a strategic level, even the most unlikely crises can be planned against.

Buro Happold’s Head of Strategic Planning Lawrie Robertson points out that most major crises are not actually Black Swans, given that they normally can to some extent be predicted. He takes Beirut as an example.

“Some of it is very hard to deal with, like the biggest earthquake or the biggest tsunami that could hit Beirut,” he says. “It is very unpredictable to know when it’s coming, but in the course of Beirut’s urban history, it’s been destroyed six times. So you know it’s there. In that sense, most things aren’t Black Swans.”

The cascade of crises to hit the Lebanese city in recent years – from fuel “brownouts” (a major drop in electrical supplies), through to the explosion in the docks, might have been predicted at some level.

“Whilst maybe a fertiliser explosion wasn’t on everybody’s lips, the governance around safety was a concern.” Robertson recalls. “We were more worried about spontaneous building collapse. You wouldn’t need an explosion or an earthquake to make some things in the city fall down – and sadly some of the most overcrowded buildings with some of the poorest residents were at the highest risk because the application of safety rules wasn’t there.”

Uncertain challenges

Buro Happold’s cities consulting team has offered critical guidance and consultancy to dozens of cities around the world in recent years, to help them to build robust urban resilience plans, through a series of projects around the globe. The Comprehensive Urban Masterplan for Beirut was one such project in 2015-16. Buro Happold was commissioned by the City Council of Beirut and the World Bank to bring a raft of strategic resilience planning specialisms to the scheme.

The action-oriented plan included a programme of key projects, prioritised according to their impact, timeframe and feasibility. Importantly for both the city and the World Bank, the plan was closely aligned to other critical frameworks including Sendai and the Paris Agreement, at the global level, and the municipality’s 2022 land-use plan at the local level.

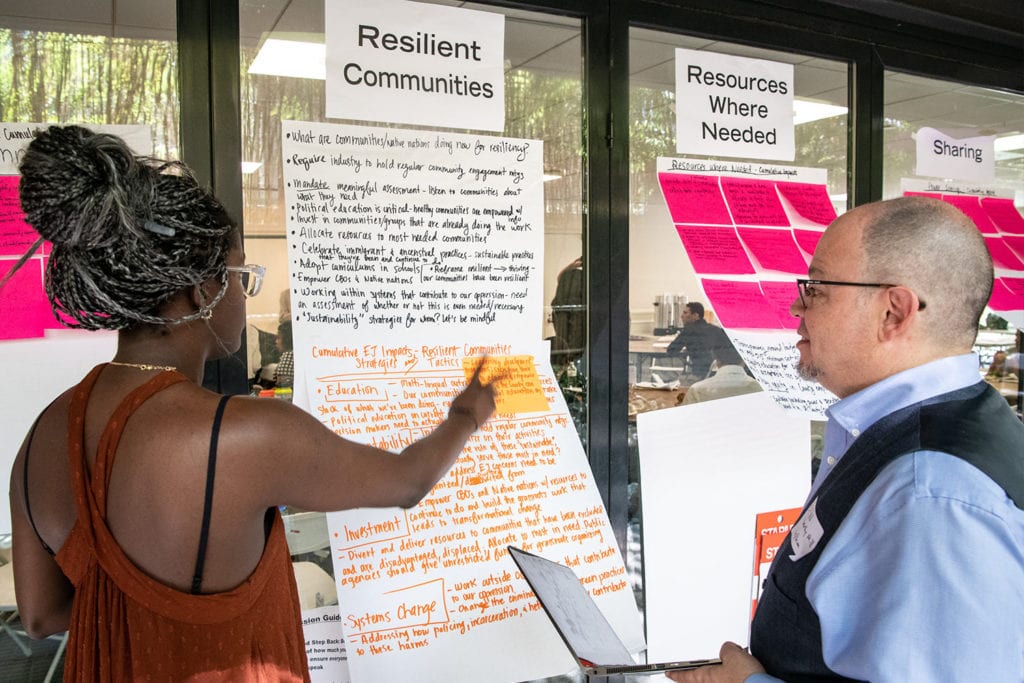

The engagement of a full range of stakeholders from government, community and business was core to establishing the city’s risk profile as it related to a wide variety of shocks and stresses. This knowledge and stakeholder participation was carried through into the development of the plan and the preparation of an implementable programme of actions.

While earthquakes represent one of Beirut’s most significant risks, the plan identified and established appropriate responses to a full range of natural and man-made hazards considering both shocks and stresses as well as relevant interdependencies.

As part of the project, the technical capacity of the municipal administration and stakeholder organisations was assessed – including a review of the disaster risk governance at national and municipality levels. This gave rise to a number of detailed recommendations for enabling actions including new protocols for the collection and sharing of critical data sets and the establishment of a cross-sectoral platform for disaster risk management.

100 Resilient Cities (100RC) is a global project funded by the Rockefeller Foundation to stimulate a focus on urban resilience in city governments. The programme, founded in 2016, created a network of 100 cities, with an aim to provide support to each over a three-year period. The principal aim of this commitment was to implement real projects, policies and programmes that have a lasting impact and ensure cities are able to withstand the certain and uncertain challenges of the future.

Buro Happold was appointed to the network as a strategic partner, responsible for delivering technical and institutional capacity building, supporting the development and implementation of customised city strategies, and facilitating stakeholder engagement across multiple cities and citizen groups.

The project, which later converted into a resilient cities support network, was focused on placing chief resilience officers into the cities and building a resilience governance framework in each of the participating cities.

The resilience strategies for the cities serve as roadmaps to build resilience, articulating priorities and identifying initiatives for immediate and long-term implementation. They also trigger action, investment and support within city government and from outside groups.

Our team supported the development of the resilience strategies for a range of cities across Central Europe and South East Asia, ensuring proposed actions were grounded in a holistic understanding of urban resilience that addresses shocks and stresses, alongside a rigorous fact base. By working closely with city officials and studying local institutions and their policies, we were able to determine how initiatives may be integrated across multiple city departments.

Partnerships process

The Indonesian capital, Jakarta, was one of the cities to benefit from our support on the 100 Resilient Cities project. Country Manager for Buro Happold Indonesia Puspita Galihresi, who worked on the project, says the city saw enthusiastic stakeholder engagement, with stresses and shocks identified ranging from food security to the resilience of digital connectivity. But she believes the greatest challenge is to maintain the momentum in the city amid political power changes.

The actions for Jakarta were taken seriously by the local government in the city. They adopted [the project’s findings] into the policy that they had and set it up as the umbrella for some key regulations. It’s not yet 100 per cent implemented, but it is getting there. They are also trying to introduce them into state enterprises. The government of Jakarta has put in a lot of effort into continuing and developing the programme.

Puspita Galihresi, Country Manager, Buro Happold Indonesia

“They have had some success on dissemination – explaining [the priorities] and engaging stakeholders in the process. We have had two [national] governments in this time, so it is more challenging when the city government is the opposition to the national government. But the progress is still going in terms of the partnerships that were set up.”

The 100RC approach was all based on building successful partnerships. By engaging a vast number of cities, stakeholders and technical experts in this process, a deep body of knowledge on common resilience challenges was accumulated, contributing to a network that facilitates the exchange of ideas, creates new best practices and, ultimately, advances a global practice of urban resilience.

“There was a lot of discussion then about what resilience was among the key agencies,” Robertson says. “A working definition that comes out of all of it is the ability to adapt to shocks and stresses as a city. Resilience for the most part can’t be about toughening everything up so that crises bounce off, it has to be more about how well you roll with the punches.”

He adds: “A city that’s doing really well overall, will often bounce back from incredible shocks. When a shock pushes a city far off track and it doesn’t come back, it’s generally because of the underlying stresses – if it was already in economic decline, if there were already enormous social inequalities, if there were already underlying climate change and resource depletion stresses, that’s what kills the city in the end, rather than the shock event.”

“So a very important part of all of this work is to get a very broad mapping of all the shocks and stresses that a city faces and particularly importantly, the interrelationship of one to another. If the big earthquake hits, it doesn’t hit the perfect city where everything’s running fine. It hits the city that we’ve got today with all of its problems.”

You could have seen the big explosion in the docks at Beirut as something that was already made much more likely by poor governance processes and when it did hit, a city in a better position than Beirut would have come back much more strongly from it.

Lawrie Robertson, Head of Strategic Planning, Buro Happold

Preparing preparedness

Other projects undertaken by Buro Happold’s Cities Consulting team in recent years have been very much about building the robust foundations of cities that would help them to be more resilient when shocks and stresses strike. The Complex Urban Systems for Sustainability and Health (CUSSH) project has been running since 2016. Buro Happold joined a consortium led by University College London and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine in a global research partnership funded by the Wellcome Trust. The project aims to develop critical evidence on how to achieve the far-reaching transformation of cities needed to address vital environmental imperatives for population and planetary health in the 21st century.

To achieve this, a team of international experts is closely cooperating in order to unpick complex issues and identify integrated solutions for the specific problems of partner cities. Cutting-edge science and systems-based participatory methods are being used to articulate visions of development, help share policy decisions, and accelerate the implementation of transformational changes for health sustainability in low, middle and high-income settings.

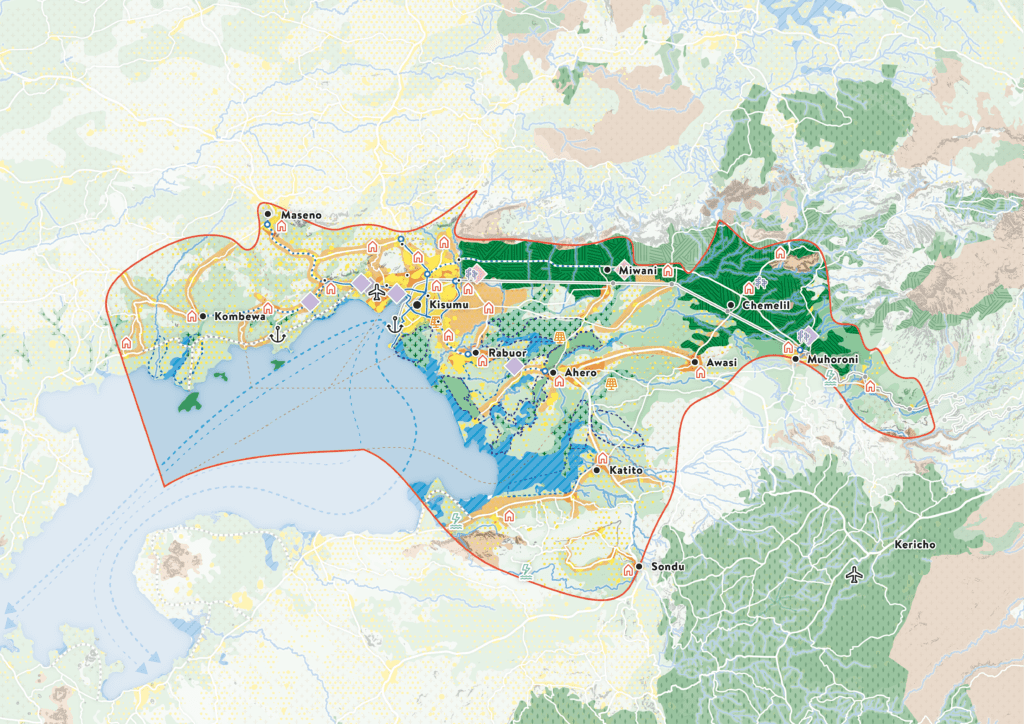

Our role in the team is to bring expertise in engaging with city governments and stakeholders on local governance and urban development projects, complementing the research expertise of the wider project team. The places we are engaging with include London (UK), Rennes (France), Kisumu and Homa Bay Counties (Kenya). We are helping to manage an iterative stakeholder engagement programme with the partner cities in the project.

During this process, we expect to gain an in-depth understanding of the challenges cities face with regard to health and sustainability and to start developing evidence-based approaches to tackle them.

Lucy Bretelle, a strategic planning consultant at Buro Happold is leading the project and helping to develop a County Spatial Planning Framework for Kisumu County. This explores how an integrated approach to spatial planning can help address complex interconnected challenges around sustainability. Bretelle says there is an urban resilience element to the plan.

“We first looked into the risk to natural hazards by undertaking high-level environmental risk assessments – mapping flood, mud and landslide-prone areas. We then also explored population vulnerability to those natural hazards as well as to the spread of diseases, thinking about urban sprawl, population density and proximity to high-risk areas.”

There is no such thing as a natural disaster – hazards are natural; disasters are manmade. It is important to think about risk to natural hazards but also population vulnerability to those. There is as much a natural element as a human risk, vulnerability, preparedness, and response to disasters.

Lucy Brettelle, Strategic Planning Consultant, Buro Happold

Knowledge is power

Robertson says urban resilience is ultimately all about this kind of self-knowledge as a city.

“You can’t be omniscient about your city, even when you’re running it,” he says. “But the degree to which knowledge is shared is often the first big difference between a more and a less resilient city.”

This process of “getting everyone around the table” was the greatest strength of the 100 Resilient Cities project, he adds.

You were in these great workshops where people who had never talked to each other within the city, were all together. Suddenly there’s an army general talking to the head of the social care system, who in turn is talking to the leader of a community district and sharing where their vulnerabilities lay. That self-knowledge does make a big difference.

Lawrie Robertson, Head of Strategic Planning, Buro Happold

He believes that post-Covid there is now more of an appreciation for the need for this kind of strategic planning for city-wide shocks and stresses.

“We’ll have to see whether it lasts,” he adds.

“But we are starting to see a shift in city government worldwide to understand that your job as a city – or for that matter a national government – for the past 20 years has been to say ‘there’s a boomtime, we can help you all get rich as quick as possible and our job as government is to optimise around that.’ The recognition that the world was a nasty place was pushed to the side, except in certain locations.”

“There is a recognition that the nastiness is coming in on all sides now – particularly climate change-led, but also with the pandemic and the return of inter-state rivalry. The role of the state to keep you safe is much bigger, so the case for doing certain things in governance terms has increased. They have woken up to the fact that citizens’ expectations for protection are much wider than they used to be.”