15 Minute Cities

The urban development concept that seeks to connect people with their community, and the wider city beyond.

Fifteen-minute cities are hitting the headlines. Developed by Pantheon-Sorbonne professor Carlos Moreno, this urban planning concept aims to create communities in which people have access to the services they need to live, learn and thrive, all within a 15-minute walk or cycle ride from their home.

The idea is gaining rapid traction. Paris mayor, Anne Hidalgo, won her re-election campaign on the back of her commitment to the philosophy and its scope to revitalise the city. Moreno is also working with the C40 global network of nearly 100 city mayors who are looking to find ways to cut carbon emissions and confront the climate crisis.

Promising to reduce reliance on cars, promote mental and physical wellbeing, support the local economy and tackle issues of loneliness and isolation, 15-minute cities could well be the future of urban planning. But where has this theory come from, and how easy is it to translate into day-to-day reality?

Tried and tested planning principles

“The 15-minute city concept is really an update of long-standing principles that sit behind the planning of neighbourhoods,” says Roger Savage, Director of the Strategies and Plans Group at Buro Happold. “It dates back to the 1920s, when Clarence Perry introduced his vision for the neighbourhood unit in the States.”

Perry developed the neighbourhood unit as a framework for planners to establish successful, self-contained neighbourhoods in newly industrialising cities. His concept married a variety of social and physical design principles to promote a community-centric lifestyle that could be replicated in an almost modular manner throughout the US.

Across the pond, Ebenezer Howard was adopting a similar approach with his garden cities movement. He placed additional focus on the importance of open spaces and public parks, principles which then fed into the new towns programme of the 1940s. When the first London plan was developed in 1943, it centred around this concept of urban villages, with the view to controlling urban growth and infrastructure development across the city. The aim was to establish communities and economic opportunities away from the city centre, while also preventing the urban sprawl that was occurring following the rise of the motor car.

“What’s new about this version of urban planning is that it is less about stopping sprawl and more about revitalisation and addressing social and economic challenges post-COVID,” says Roger. “There is also a new emphasis on the climate agenda and net zero, with a focus on reducing car use and promoting more sustainable ways of living and working.”

Benefits of 15-minute city life

This very much supports public health and encourages a sense of community.

Roger Savage, Director, Strategies and Plans Group, Buro Happold

The benefits of the 15-minute city are myriad. Providing people with access to parks or green spaces encourages interaction and integration, helps combat isolation, and builds a sense of community. Establishing shops and amenities provides a welcome boost to the local economy and encourages walking or cycling over car use, where possible, which is better for the environment and people’s physical health.

“Other elements critical to creating a successful 15-minute city are social infrastructure, such as schools and health facilities, as well as cultural venues like community centres and libraries,” says Roger. “It’s also about designing the streets and the spaces to support conviviality. That’s partly about giving priority to walking and cycling, as well as providing access to green spaces like parks and children’s play areas. This very much supports public health and encourages a sense of community.”

Of course, each neighbourhood starts off with its own endowment of services and infrastructure, as well as its own unique social mix. Inevitably this means that some areas are more affluent than others and may have access to more resources. That’s why it’s vital to assess each area on an individual basis, finding ways to improve quality of life in the local area while also providing excellent links to the wider city for access to jobs and high order services, such as higher education and entertainment facilities.

Buro Happold and the 15-minute city

We’re all about solving complex challenges.

Roger Savage, Director, Strategies and Plans Group, Buro Happold

Buro Happold is well-placed to understand and respond to the varied and differing needs of these complicated urban projects. Since its inception in 1976, the practice has held connectivity, community and sustainability as central tenets of its work. International in scope and agile in approach, the Cities team brings with it a wealth of perspectives around urban planning and strategy.

“We are all about solving complex challenges,” says Roger. “Our team contains people with interdisciplinary backgrounds who can navigate and work with all the different stakeholders, acting as a bridge between developers, landowners, public sector partners, and the community.”

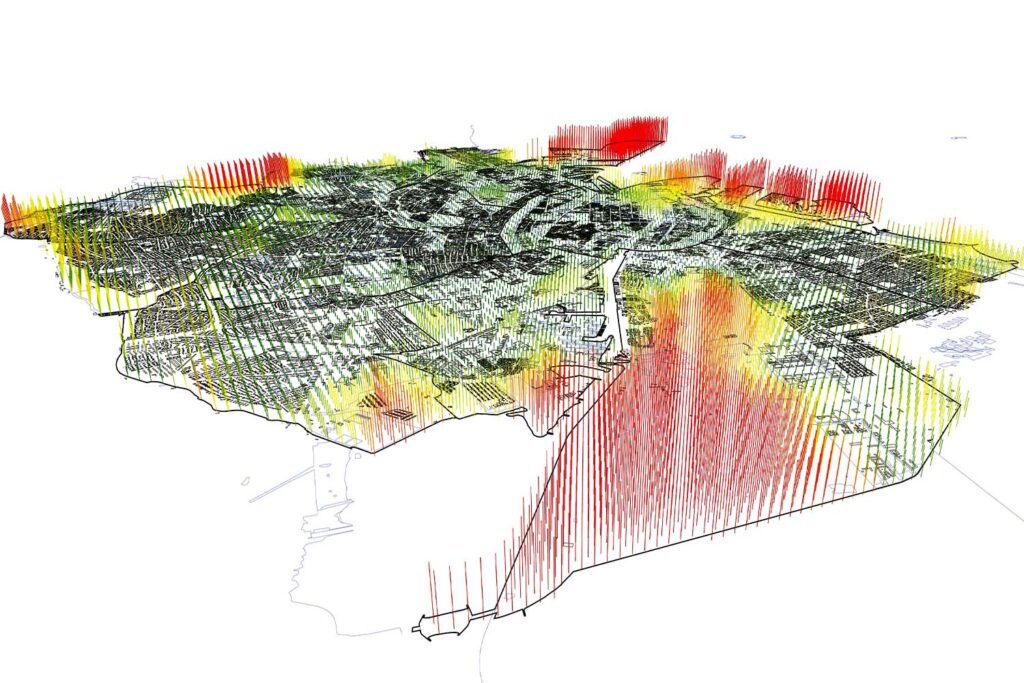

On a typical project, Buro Happold will draw expertise from across disciplines such as urban planning, economics, GIS and geospatial analysis, as well as infrastructure, transport, ecology, environmental and sustainability. Other specialists in disciplines such as water, energy, inclusive design, and flood risk management can be consulted according to project demands.

“As well as setting objectives and shaping proposals, we are also closely involved with the funding and delivery aspects of our projects,” says Roger. “This can mean seeking public sector funding, or looking to community, philanthropic, and other private sources as well. Securing that funding is dependent on making a strong economic case for development by identifying, assessing and communicating the benefits that can be delivered.”

Building a successful community

As with all our work, we try and make this process as inclusive as possible.

Roger Savage, Director, Strategies and Plans Group, Buro Happold

For a project to be successful, there needs to be coordination and partnership between all of the different public sector bodies and service providers, as well as community organisations and other stakeholders. Roger and his team know that the devil is in the detail of this process of negotiation and compromise. There will always be necessary trade-offs, and Buro Happold is skilled in aligning differing perspectives to attain the best outcomes, and defining a pathway to deliver maximum benefit for each place.

“There’s always a dialogue to understand the requirements of each community we work with,” says Roger. “What do the local people want? What are the public sector stakeholders looking for? What is the developer hoping to achieve? Then there’s a process of navigating and negotiating the responses to establish priorities. Sometimes we have to find a balance. This may be, for example, the percentage of affordable housing versus providing new schools, or improvements to the streetscape and public realm.

“That’s why there’s a lot of stakeholder engagement and consultation involved in all the planning work that we do. From service providers and public agencies to the communities themselves, we will engage as many people as we can through measures such as community workshops, forums, and surveys. As with all our work, we try and make this process as inclusive as possible, employing measures to reach historically under-represented groups and finding tools that can be accessed by a variety of people according to lifestyle and need.”

Case study: East Midlands Development Company

Buro Happold is currently working with Areli, the East Midlands Development Company and other project partners to help revitalise new and existing sites across Nottinghamshire and Leicestershire. The aim of this ambitious project is to establish the area as a template for net zero carbon development, world class connectivity, biodiversity and nature recovery, and connection across communities.

“One of the opportunities we’re involved with centres on revitalising the existing community of Toton,” says Roger. “Originally, there was going to be a HS2 station in the town. That is no longer happening, so our challenge was to find alternative catalysts for growth and regeneration.

“The strategy proposals incorporate anchors around health and wellbeing, along with refurbishment of the former Chetwynd military barracks to create new housing. Our plan also integrates elements towards achieving net zero and opportunities for resource circularity in terms of water and energy use, as well as waste recycling. A proposed extension to the Nottingham tram network will see Toton enjoy improved links with the wider area.”

Roger and his team are also working on a series of new neighbourhoods in nearby Rushcliffe and North West Leicestershire. These are intended as standalone communities that follow 15-minute city principles, each supporting its own primary school and local centre, as well as having good public transport links and easy access to the surrounding countryside.

“There are knock-on benefits of these schemes as well,” says Roger. “Because of the scale of the development proposed, it’s enabling improvements to the Attenborough Nature Reserve, a big wetland area along the River Trent. Traffic-free links to the Erewash Canal and the River Erewash are also planned, opening up blue corridors for both residents and visitors to explore.”

The future of the 15-minute city

Built on established planning principles reimagined to address modern urban issues and the climate crisis, the 15-minute city concept has gained support from both private developers and the public sector across the UK. Policies to encourage this approach are being built into local plans, but explicit nationwide guidance to support implementation is still some way off. But with cities such as Oxford, Bristol, Canterbury and Sheffield having embraced the approach where interventions have been implemented, it should only a matter of time before we see the return of thriving communities at the heart of our cities.