How to design in happiness

Can good design make us happy? Given that we spend most of our time in buildings, should we not have a better understanding of how they make us feel?

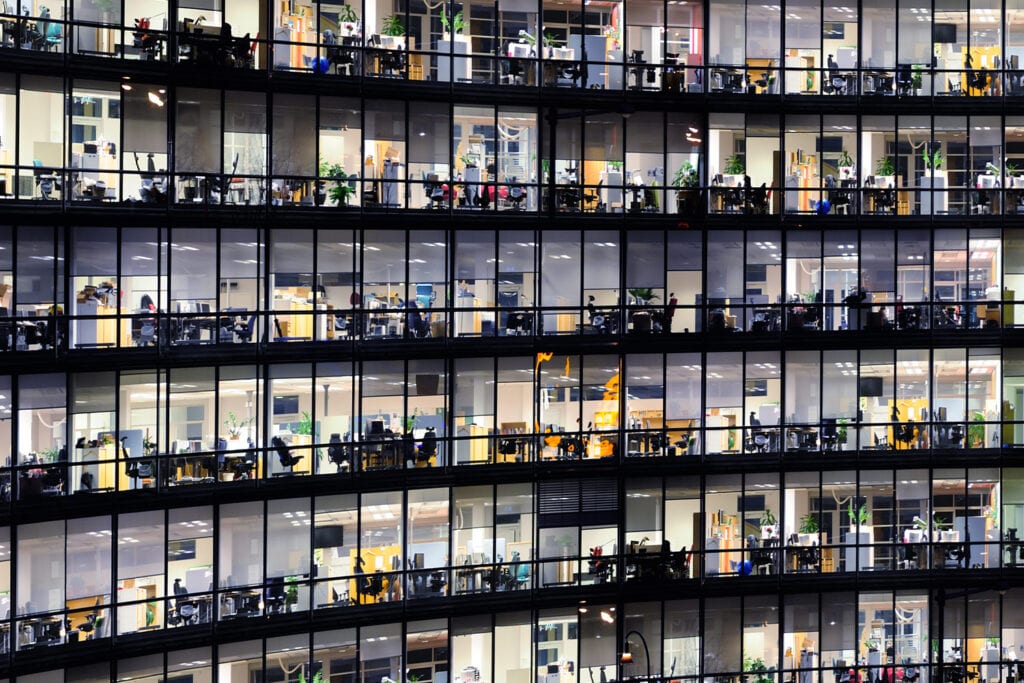

The built environment has come into sharp focus during the Covid-19 pandemic. With many of us now working remotely, the intersection between design and mental health has become ubiquitous. There is no doubt that a poor quality working environment affects both our physical and mental health. It can be argued that Covid-19 has exaggerated the UK’s mental health crisis exponentially.

There is an inextricable link between the built environment and psychology in terms of how our surroundings affect our mental health. Environmental psychologists have been researching this since the 1980s, with positive psychology gaining prominence in the 1990s. Their research has proven that good design makes us happier as it supports pleasurable and meaningful experiences.

Lockdown has offered new perspectives on how buildings should be designed for functionality, mobility, safety and wellbeing. Building design and construction should take a more nuanced approach rather than prioritising return on investment. Instead, buildings should focus on the human experience.

The science of happy

We can all identify with the feeling of happiness. A euphoric and elevating state of mind, happiness transforms our disposition. In the emotional hierarchy, it is the “gold standard”. It is what we strive to achieve during our lifetime. Happiness goes beyond a positive mood. It is a sense of deep contentment that incorporates leading a life of purpose and meaning. Above all, happiness lies in human connection.

Happiness is a relative term so therefore the science behind happiness is highly contextual. Happiness can be influenced by several factors, but it’s widely recognised that our physical environment has a major impact on our health, wellbeing and productivity. The medical community has been studying what makes human tick since the late nineteenth century. Positive psychologist Sonja Lyubomirsky attributes happiness to three sources: 50% is based on your genetics, 40% is environmental and 10% is attributed to intense experience. If 40% of our happiness can be determined by our physical environment, architects and engineers have a responsibility to design mindfully.

Designing for our mental health

Buildings are the backdrops of people’s lives, and yet it is no secret that staying indoors for prolonged periods of time affects our mental health and heightens feelings of stress and anxiety. Given that our physical and mental health contribute to a positive emotional outlook, how we feel in a space is just as important as what we are doing in that space.

It is well known that we spend the majority of our time indoors – 90 percent, in fact – and so it is absolutely essential that we rethink our relationship with the buildings around us.

Ben Channon, Architect and Mental Wellbeing Ambassador at Assael Architecture and author of Happy by Design.

Ben advocates for wellbeing conscious design in all buildings. This type of design encourages built environment professionals to pursue elements of design that improve our livelihoods by prioritising the end-user above all else.

Ben’s book explores these themes in detail, exploring how environmental factors such as colour, biophilia, light and ventilation impact our relationship with buildings, and ultimately the people we encounter in these buildings. He discovered some surprising insights about how our happiness is affected by our surroundings. For example, “messy homes stimulate the release of stress hormone cortisol. It is not surprising Scandinavia place so much importance on well-designed storage,” explains Ben.

At its core, design is about solving problems. To truly design in happiness, what are the design fundamentals? Our experts identify nine quantifiable criteria for built environment design:

| Lighting | Use of natural light boots vitamin D | |

| Ventilation | Air quality, thermal comfort and large windows | |

| Nature and biophilia | Views of the outdoor landscape and indoor plants | |

| Acoustics | Noise level absorption | |

| Colour | Colours evoke certain moods e.g. red boosts creativity and green is calming | |

| Proportions | High ceilings and large rooms | |

| Position | Interior layout and exterior positioning | |

| Inclusivity | Disability and additional needs access | |

| Community | Facilitating social interaction | |

Taking inspiration from nature

According to the United Nations, 55% of the world’s population now live in urban areas. This statistic is set to increase to 68% by 2050. We have an in-built affinity with the natural world, and yet, we spend most of our lifetime indoors. This can often attribute to feeling lonely and isolated. Poor quality ventilation, low ceilings, small rooms and lack of natural daylight – all these environmental factors are not conducive with good mental health.

Biophilic design is therefore an integral part of designing for happiness. We are highly sensory beings who value connection, whether that be with other human beings or to nature. Buildings need to serve the communities that use it.

As Ben reiterates, “In the UK alone, one in four people will experience problems with their mental wellbeing. And as we spend 90 percent of our time inside buildings, the spaces we live and work in are going to have a significant impact on our physical and mental wellbeing.”

Happy design is inclusive

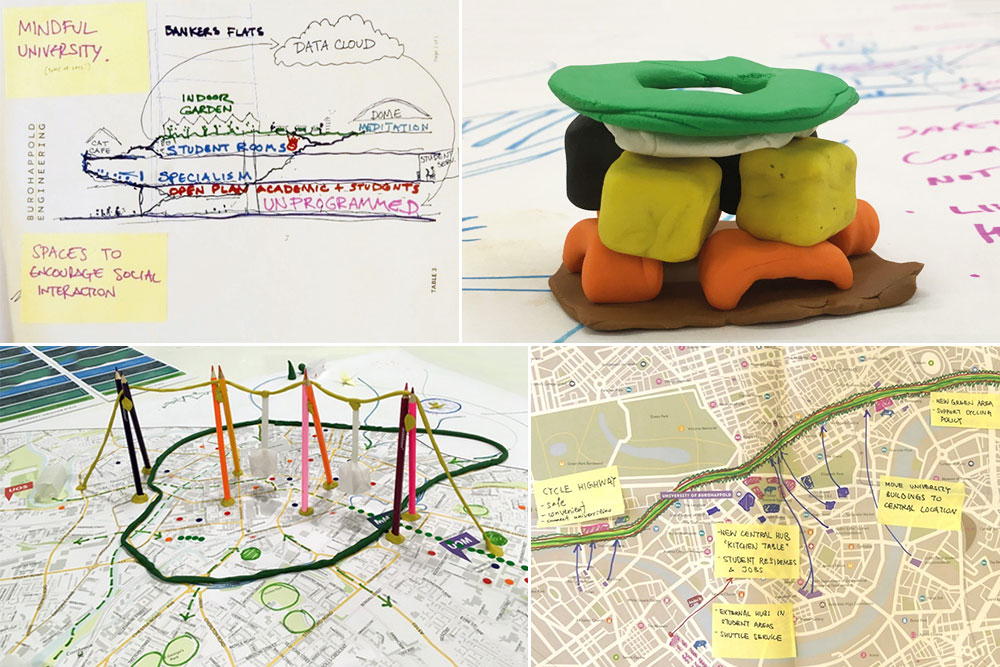

Happy design is intuitive by nature. It should delight not frustrate and make the end-user feel calm, safe and in control. Users should feel free to move about the space, curating their own sensory experience. Ultimately, it is about feeling connected – to the built environment itself and the people you are with. As engineers and designers, we should be “designing to avoid loneliness and improve interaction between people” says Dr Mike Entwisle, Buro Happold Partner and Global Education Sector Lead.

Society contains a diverse range of people, all with specific needs, so the built environment should reflect this. We are all unique human beings so will experience the same environment differently. As Buro Happold’s Senior Inclusive Design Consultant Jean Hewitt explains, considering all human needs when designing buildings is key for inclusivity.

Putting choice and control at the heart of good design. Those with additional needs need choice and control over their environment in order to feel calm and secure within buildings.

Jean Hewitt, Senior Inclusive Design Consultant at Buro Happold

Inclusive Design is about understanding the concept of universal design; the needs and concerns of people, what they want from an environment and the experience they will have within it. That’s why inclusivity is so important when we consider designing for happiness.

The International WELL Building Institute (IWBI) is leading the global movement to transform our buildings and communities in ways that help people thrive. Similarly, research at the Delft Institute of Positive Design formulates effective strategies to help designers increase our wellbeing and long-term happiness. A healthy society makes the world a better place. The aspiration of most designers is to make a positive contribution to society with their work.

Putting students first

A sector of the built environment that dramatically impacts mental health is the university campus. Where you learn is as important as what you learn. The building aesthetics, location and layout of a university can make or break your student experience. Buro Happold is researching and exploring how the physical environment can affect student mental health. Our findings conclude that connectivity is vital for good mental health.

We have surveyed over 5,000 students globally and found that a staggering 44% considered the design of university facilities to be average or poor, with issues of capacity and physical connectivity called into question.

Dr Mike Entwisle, Global Education Sector Lead at Buro Happold

University students and staff need to understand the role of the environment and community in protecting mental health. As Mike points out, “none of the university league tables in the UK or beyond reference the quality of the environment in determining national and global rankings. I think these are real failings of the system that we have in terms of how people choose universities.”

Considering these findings, the design of university buildings needs to change dramatically. Universities must learn to put students first. Students are now looking for multi-functional environments; spaces that are a hybrid between work and leisure. Communal spaces need to serve all aspects of student wellbeing and safeguard them in this initially unfamiliar environment.

Research carried out in 2018 by UK charity Mind found that 60-70% of university students struggled with mental health issues. Research by the Mental Health Foundation in 2018 stated that “75 per cent of mental health problems start by the age of 24,” so university students are a high risk group.

High fees, and high expectations, mean that those attending UK and US universities are already under pressure to succeed. The atmosphere at some institutions is highly competitive and students can be exposed to stress, anxiety and other mental health pressures.

The complexity of student mental health vs societal expectation more generally means that young people feel more pressure to achieve than ever before.

Adam Poole, Associate Director and Special Strategic Projects Lead at Buro Happold

Imposter syndrome and comparison culture are inherent to Generation Z. It has never been more important to recognise that the social aspects of university make students feel that they belong. “That fundamentally comes down to designing to avoid loneliness and to improve interaction between people. If you improve the environment it improves the outcome for everyone,” says Mike.

Happy design benefits all

One Buro Happold project that embodies the fundamentals of happy design, principally facilitating human interaction, is The Forum, University of Exeter. Connectivity was the focal point of the design process, using natural light, cutting-edge acoustics and tactile materials like timber and glass to bring the outdoors in. The gridshell roof structure creates a multifaceted environment for learning, teaching, research and collaboration. The centrepiece is the hub of the university, providing state-of-the-art educational and pastoral facilities for everyone at the institution.

This type of work is incredibly important to Buro Happold. After all, prioritising happiness in our building design, especially within the Higher Education sector is benefitting the future generation of engineers, architects and designers.

Priorities in building design are changing. Clients not only want sustainable buildings but environments that positively impact society. Buildings must be designed to make happiness a reality for everyone. We all want to be happy. So, if building design can tangibly contribute to our happiness then that is a low-hanging fruit.