Our cities are our communities – working collectively to foster sustainable cities for all

The current Covid-19 pandemic has laid bare the economic, social and environmental value of local communities and their role in contributing to sustainable livelihoods.

As this year’s UN World Cities Day recognises, this is ever more apparent in lower-income and informal societies, where unpaid care and support services often go unnoticed.

However, even the higher-income cities and their citizens have not been immune to a series of challenges that Covid-19 has pushed to the forefront of everyday life. Will the recent trends towards urban living continue despite the inherent threats that intensity of population promotes? Or will it slow or even reverse?

At Buro Happold, we have worked with communities that are growing rapidly, that are stagnating and that, in a few instances, have shrunk radically. Responding to this pandemic and any that might happen in the future represents yet another dynamic that demands adaptive and resilient measures. But to be effective, these require the active and equitable involvement of communities – and that will only be possible through ever closer engagement with the citizens of those communities.

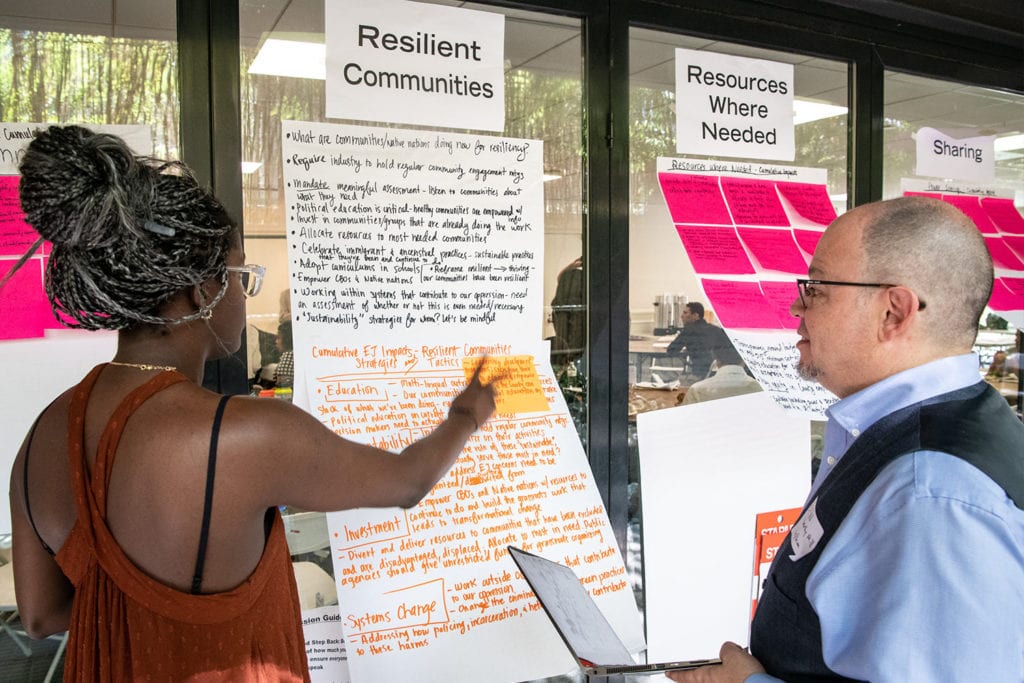

This premise prompted us to undertake a series of Design Sprints – by now thoroughly tried and tested – and consult with the communities represented within the cities where we have offices. We organised a series of workshops across our regional offices, led by our agile, co-creative, thinking and innovation programme called the Urban C:lab.

Despite the diversity of our communities, several key themes are notable in their recurrence. They are informing how we recognise the innovative, creative, resilient power of the community actors and networks who will foster quality of life in our cities. These are those who will promote wellbeing and an inclusive economy, as well as bringing social justice to repair climate inequity while protecting biodiversity.

Interestingly, they echo some of the longstanding guiding principles of our work.

Adaptability for community assets

We were surprised how quickly and effectively we adapted, repurposing our home spaces with incredible pace and agility. We had to redefine every square inch with new use function, reinventing these spaces throughout the day and every day.

For those living in very different shapes and forms of density and space, constrained places, a lack of amenities or ownership negatively impact the capacity to adapt. A lack of clear separation protecting the vulnerable in a makeshift home-to-office building means depriving domestic workers of income when their workplace is another family’s home.

In our work, we reclaim underutilised assets to provide agency for communities to deliver on adaptation. These have included repurposing an unused gasometer in Edinburgh and restoring a derelict railway viaduct to regenerate Folkestone and its harbour. We have drawn up strategies around how to reuse leftover public infrastructure in a move towards integrated urban development, increased connectivity, and enhanced access to public space and amenities.

We recognise the significance of getting the strategy right for our communities so that disruption is minimised and resilience built when these interventions are needed. This work is manifest in our vulnerability assessments and climate action and adaptation plans from California to the City of London.

Flexibility for design resilience

This need for rapid adaptation is often a by-product of over-design that yields inflexible built environments. Communities can effectively make and maintain environments if the underlying structure is structurally and financially robust and the legislative framework conducive to change.

When engineers are hardwired to solve problems by new design, future redundancy of infrastructure requires retrofit, resulting in sunk costs. Opportunity costs of ‘designing to tight fit’ are deprivation and unaffordability: we strive to mitigate this by introducing flexibility from the building-scale to city-scale.

Extensive investigation into how we can reconfigure streets for greater flexibility through pedestrianisation or cyclability unlocks opportunities to reclaim public rights of way and the kerb. This provides the potential for green infrastructure and recovering revenues, say from loss of car parking spaces.

Access and equity to shared capital

Cities agglomerate innovation that can overcome a lack of access for disadvantaged communities. From facilitating smoother transitions between modes of transport to enhance mobility, to making the economic case for green infrastructure, micro- to macro-solutions can break the political deadlock that deprive adaptability and flexibility.

In places like the London Olympic Park, a legacy of truly inclusive access will require time, but we take courage from the resilience and robustness of the place, represented by the increasing diversity and density of public use. From complete riverside regenerations to a single bridge construction, enhancing connectivity helps create healthier environments and can yield outcomes not intended by design, but innovated by the very communities who reclaim that piece of public asset.

Culture of behavioural change for re-invention

Policy change and interventions to facilitate these negotiations will require behavioural change in much the same way as we found when we learned to let go of our fears and possessions. When we can once again congregate in cultural spaces to share our learned experiences, cities as cultural hubs will re-invent themselves.

Northern English cities that have gone through these cycles know this too well. Places wither and flourish. A design approach of maximum use benefit with minimal intervention that respects inherent culture can deliver the right message to communities who are stuck in a false choice between dereliction and unfettered development.

Human-centric, empathetic design for sustained social bonds

Underlying all of this is human-centric, empathetic design to unlock the creative force to give back to communities.

When our engineers delivered a business case to process excavated material underneath the Tottenham Hotspur Stadium, 700,000kg in CO2 emissions were saved, along with increased pedestrian and cyclist safety and a number of local jobs. An even greater benefit was a new community facility emerging from re-laying a school playground adjacent to the stadium, creating a significant income stream for the community.

To get this approach right, early engagement with community stakeholders is essential. We need to understand where priorities lie, where gridlocks are, how social value can be extracted, and what gaps in skills might be filled. From Leeds to Leith, we have embarked upon workshops to draw net zero carbon strategies for local communities, or to investigate co-benefits in marine sustainability and arctic tourism for national governments.

In this transition

Cities are first and foremost agglomerations of human capital and interaction. They accumulate, create and innovate knowledge – but when they fail to distribute these equitably, our livelihoods are disrupted. Naturally, this will be different in different locations, but the focus is clear.

As we observe this year’s UN World Cities Day, we are adamant that we must empower our communities – and be empowered by them. They and we must adapt in order to include and to recover, gaining resilience through this transition and beyond.

Our cities are our communities.