How could considered design increase research effectiveness?

How do we as designers create research facilities that inspire and connect, whilst adapting for the changing needs and demands in the sector.

Lack of funding, a crowded market, a fragmented community – these are just some of the problems that the science and technology industry faces today. And tackling them isn’t simply about policy change, although government can certainly help. Fostering innovation is a task for everyone. That’s why Buro Happold and ADP invited a range of prominent thinkers from across the science and tech community to join us at a “Design Sprint”, working together to find solutions to some of the industry’s biggest problems.

The event took place in the Dovecot Studios in Edinburgh, a converted Victorian bathhouse that’s now home to a world-renowned tapestry studio. This space encapsulates many of the values we were trying to pin down: a site that attracts the most creative thinkers and makers, with close links not only to its city but to the wider world.

Keynote speakers:

David Parfrey, Executive Chair of Norwich Research Park

Jon Roylance, Director of Higher Education, Science and Research, ADP Architecture

Becky Hayward, Associate Director and People Flow Consultant, Buro Happold

To help spark debate, we started the afternoon with three keynote speeches. David Parfrey from Norwich Research Park set the scene with his image of the Valley of Death, where scientists and researchers stand on one peak of a mountain with society on the other. The problem is this vast gulf between them. As David sees it, we can start to bridge that gap by designing our science parks with people – real people – at the forefront of our minds.

Next up was Jon Roylance, Director from ADP. Jon used two examples from ADP’s own work to show how these innovative hubs can act as “anchors” for their wider regions. A good science park not only gives local talent a rooted, well connected community in which to thrive, but also feeds back the fruits of that talent to the towns and cities that surround it.

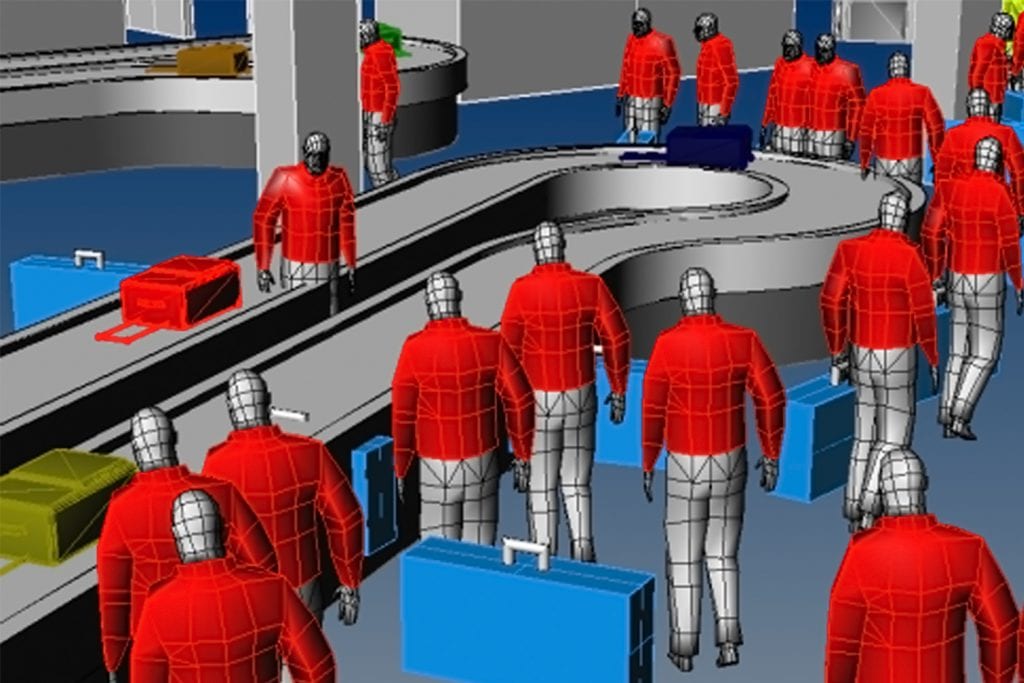

Our third speaker was Becky Hayward, Associate Director from Buro Happold, who asked the question: “How do you make a better experience for people in their working life?” The answer, as Becky sees it, lies in how we see data. We collect huge amounts of data now on every aspect of a workplace, and this can seem overwhelming – but viewed in the right way, that data can also create magnificent opportunities. A good example is the East Bank district on Stratford Waterfront, where Buro Happold built a model of day-to-day life based on architects’ sketches, and used this to test everything from the relationships between buildings to the placement of individual trees.

Question One:

An innovation start-up is looking to take a building on a science/research park site. They are likely to have a future GMP-certified process, and as a company strongly value the promotion of health and wellbeing in the workplace. What would their ideal building be?

The first step for this group was figuring out that conditions were necessary for a start-up like this to exist. A GMP-certified process is an expensive investment for a young company, and a university-funded building therefore seemed a more likely setting than a privately funded site. As the ideal building took shape, the group identified three core zones that would define its layout:

- A “thinking” space for PhD students with ideas and innovations

- A “doing” space for labs and write-ups, to develop and test ideas

- A “making” space for manufacturing the final product (the GMP area)

A building like this would need to support modern working practices – most importantly, the flexibility for people to decide how and when they work. The group therefore designed the site to remain open for 24 hours a day. Workplace wellbeing becomes even more crucial on sites like this, and there was plenty of discussion around how to design wellbeing into the building: with a rooftop exercise and recreation space, for instance. As these ideas crystallised, the group created a physical model of the building, using craft materials to represent the overall structure, relationships between spaces, and sustainability and wellbeing features.

Question Two:

A mid-to-large agritech company is reviewing options to remain and expand on a science park campus site. How can the campus be developed to accommodate them as they continue to grow?

This question gets to the heart of what makes a successful science park: sustainability. When we think of sustainability we usually think of environmental sustainability, but closely linked to this are a host of other kinds, from financial sustainability to social sustainability. How can a science park sustain continued growth and change – especially under competition from over 100 science parks across the UK? And as this group discussed, it’s not only other science parks which can attract existing tenants. Brown field sites in the heart of cities are increasingly being converted into innovation districts, and the challenge becomes understanding the potential values of a site that’s distanced from those urban cores. The group therefore decided not only to extend accommodation for the agritech company under question, but also to develop the wider site in ways that could provide a positive alternative to city working.

Out of these conversations grew an adapted masterplan for the site, with new lifestyle, retail, and cultural facilities giving an attractive alternative to inner city working. The group also left open the possibility for further development in new directions – the most obvious being housing. Sustainability of every kind was the lifeblood of the site, with flexible spaces supported by cycle paths, a walkable core, green spines, an internal electric shuttle, and the option to introduce a park and ride system

The group concluded that there are six ingredients that are essential to a modern, sustainable science park:

- Mixed-use developments, with an element of housing in the longer term

- High density

- High-quality public realm

- A focus on low-carbon mobility

- Permeability with easy wayfinding

Continuity – with a vibrant central core and a curated offer of events, activating the site all day and throughout the year

It’s very much about these shared spaces

Richard Walder, Buro Happold

Question Three:

What are the essential ingredients to create a world-leading innovation ecosystem?

Exploring a number of examples of innovation ecosystems, this group developed an understanding of two ways in which innovation can come about. It can grow organically, serendipitously – in other words, through processes which are hard to foresee or control. Or it can be triggered by a particular catalyst, such as public investment in a particular industry, or a certain business choosing to relocate.

The key question for all of this is: “Why here?” Innovation is contingent on a huge range of visible and invisible factors – so if we’re looking to support it, we need to have an awareness of those factors, of the context and unique values of a place. The answer to this question informs the whole approach, which is as much about choosing what not to do as choosing what to do. After all, nothing stifles innovation like a misplaced policy or a short-sighted reaction.

So much of innovation is about chance encounters – and while these are impossible to orchestrate by their very nature, designers and developers can still think carefully about how to enable those encounters. Something as simple as the placement of a door can hugely increase the opportunities for unexpected interaction, and while no one can say for certain that it will “generate” innovation, it could just allow for that serendipitous meeting of minds that sparks a great idea.

The group identified three key ingredients that these ecosystems would need:

- A focal point (either a literal, physical place, or a virtual one)

- A common purpose

- Talented people

The catalysts that would support these ingredients are funding and market applicability. If successful, the ecosystem would then achieve three important outcomes:

- Helping people to create new things or ideas

- Enabling them to scale those products or ideas

- Getting those products or ideas adopted and on the market

Accept that an ecosystem evolves. You don’t make it –it evolves.

Diarmaid Lawlor, Scottish Futures Trust

Contact

Contributors

ADP

Jon Roylance

Graeme Feechan

Siobhan Davitt

Tom White

Tristan Rabaeijs

Guests

Cambrex

City of Edinburgh Council

Heriot-Watt University

iDEA

Savills

Scottish Futures Trust

The Roslin Institute

University of Edinburgh